Blum & Poe Broadcasts presents free and public access to scholarship and writerly ponderings from our publications archives and network.

In focus this week—a conversation between Charles Gaines and Henry Taylor, originally published in Henry Taylor: The Only Portrait I Ever Painted of My Momma Was Stolen (Los Angeles: Blum & Poe; New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018), the first comprehensive monograph on Los Angeles-based artist.

Charles: How are you doing Henry?

Henry: I'm doing pretty good, Charles. Pleasure to be here.

Charles: I’ve read everything that’s been written about you, at least what I could get my hands on.

Henry: That’s pretty darn thorough.

Charles: We can start by asking you if you can describe your practice. What kind of work you do? Do you call yourself a figurative painter?

Henry: Are you asking what I call myself?

Charles: Well, I read somewhere that you said that.

Henry: Oh, ok, yeah. I might have said that. But sometimes I’m reluctant to say that... sometimes I find myself trying to be more appeasing than at other times. I might have said figurative to the person interviewing me.

Charles: Why are you reluctant, you do paint figures, it doesn’t go unnnoticed.

Henry: Hell no, no it’s not unnoticed.

Charles: Then for you a figurative painter is only a category of art history, it’s only about attaching yourself to a genre or type of painting.

Henry: Yeah, when I say that it might be the reasonn it’s nice when they can categorize what you do. When you go to the supermarket you want to know where to go for milk.

Charles: It makes it easier to have a conversation. But would you mind telling me what might be the problem with that term? What troubles you about being characterized like that? Is it too restrictive?

Henry: No no, no...I don’t know why I sometimes react or respond that way. When I think about it in the historical sense, “a portrait painter,” I say naw, that ain’t me...I’m not feeling it that way. I never said it like this before but maybe I picked up this crack addict off of skid row, or maybe it was a panhandler at McDonald’s...so the whole interaction with the figure is different because I’m doing something different than just making a portrait. Obviously there are different histories as related to portrait painting. Let’s consider the people who sat for (Vincent) Van Gogh or (Toulouse) Lautrec. Lautrec painted prostitutes and probably drug addicts and people who...

Charles: [laughing] Is painting people a form of painting your experiences through people?

Henry: In painting that one person, maybe what I put on it, it seems like more than that. But I guess at the end of the day, it is a portrait. It’s like we’re talking about athletes, like this one gymnast who did this amazing move but it was illegal. Ok, I'm going off on a tangent

Charles: In many ways your portraits are a visual biography of the sitter. You are bringing attention to him or her, but there is also an autobiographical element.

Henry: And this (idea of the portrait) is not a problem. But sometimes I tell myself, “I wanna get away from that.” Somebody can call you a Negro, they can call you black or African American. Sometimes you are more receptive to those labels. But then other times I’m like, “whatever!” So there’s a little inconsistency there on my part, ok? But I was also going to say it’s like if you’re playing rock and roll but you want to play jazz!” And they keep saying your’re playing rock and roll—and maybe you haven’t made that jazz album yet. Then you say just let it go, I'm gonna continue to work, whether its jazz or Rock and Roll. So sometimes it’s what’s put out there about you, but at the end of the day you’re gonna make the work anyway.

Charles: You are saying that you’re not restricted by these labels and categories. But beyond that it is about your interest in people. Quite early in your life and beyond the realm of art you had this interest in people. Perhaps we can say that portraiture might be the means by which you can express this interest.

Henry: I wonder if it also has to do with just sharpening your skills. If you like baseball sometimes you just go out there and hit. I enjoy watching golfers hit balls, the repetition...to me painting the figure is just training.

Charles: Training?

Henry: Just draftsmanship.

Charles: You’re bringing it back into the realm of art again. I was trying to stay outside of art. I know you’re interested in making paintings of people, but would you say you have a really a powerful interest in people themselves, beyond art?

Henry: Yeah, yeah...

Charles: But what would that be?

Henry: I probably don’t think too much about it but when I think about my life...I mean, I know how I interact with people. I know that I make paintings of people like the guys sitting outside my studio door. I worked ten years at the state hospital but I did not plan to become a nurse or anything—it just happened. But maybe it’s empathy. Or maybe it’s about family. I remember going to the store with my mom and going with my nanny and observing people and their relationships—a lot of things like that. I guess I do think about that and also as a source of inspiration sometimes. Like...when you start to think about people, you start to think about the truth. When I was in Haiti I saw a little boy lying in the street; he had just got hit by a truck [smacks hand]. I was just like, “Jesus, get up boy, get up!” I saw him there, lying right here. Man, I wanted to see that boy get up. Then I started to see the blood start to flow from his body. A Spanish man hit him. All these people gathered around him, put him in that man’s truck, and rushed him off to the hospital.

Charles: I understand, you have this great empathy, it’s part of you.

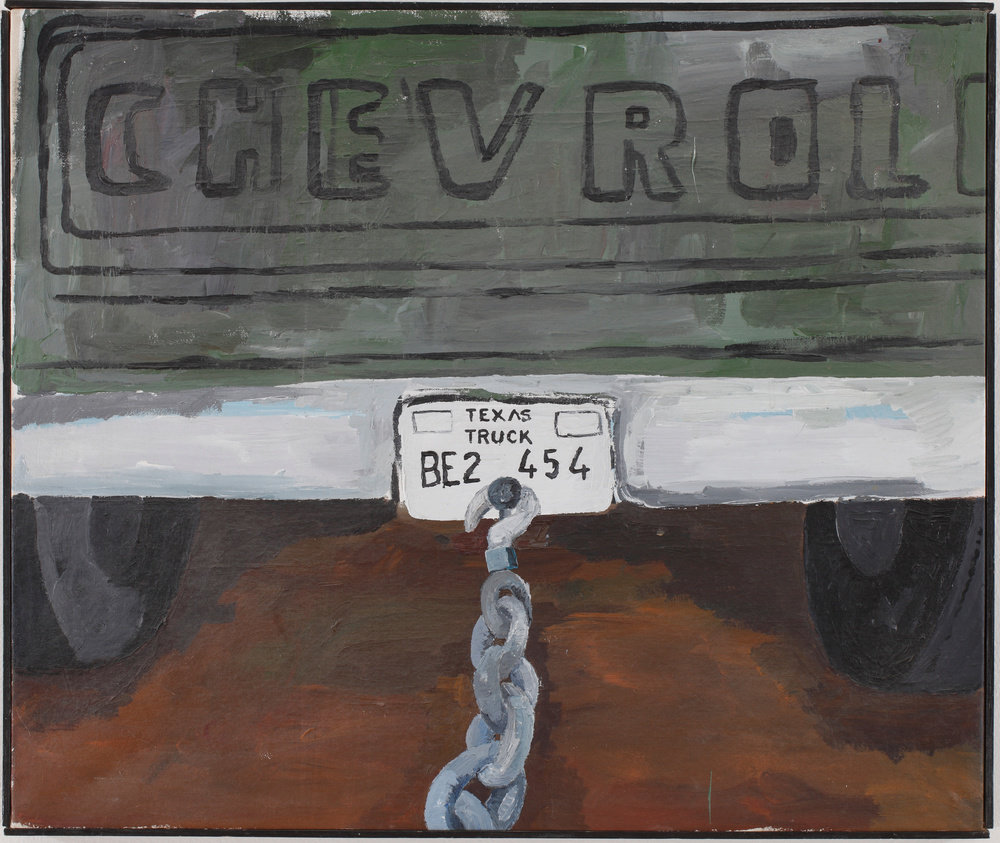

Henry: Yeah, I guess so, I can be in denial sometimes, I’m like, “Oh I don’t want to be categorized.” But hell. Peter Eleey said to me at my MoMA PS1 show, “All your paintings have people in them except for one. Can you recall which one?” I couldn’t think about the painting that way because even though there wasn’t a figure, that painting was about a person.

Charles: Do you remember the name of the painting?

Henry: Yeah, too much hate, in too many state [2001]. It was about a black man, James Byrd Jr., who was chained to the back of a pickup truck and dragged to his death. I was related to a guy from that same part of Texas where they dragged Byrd.

Charles: I remember that incident and the painting.

Henry: The painting was of just the chain connected to the back of the truck.

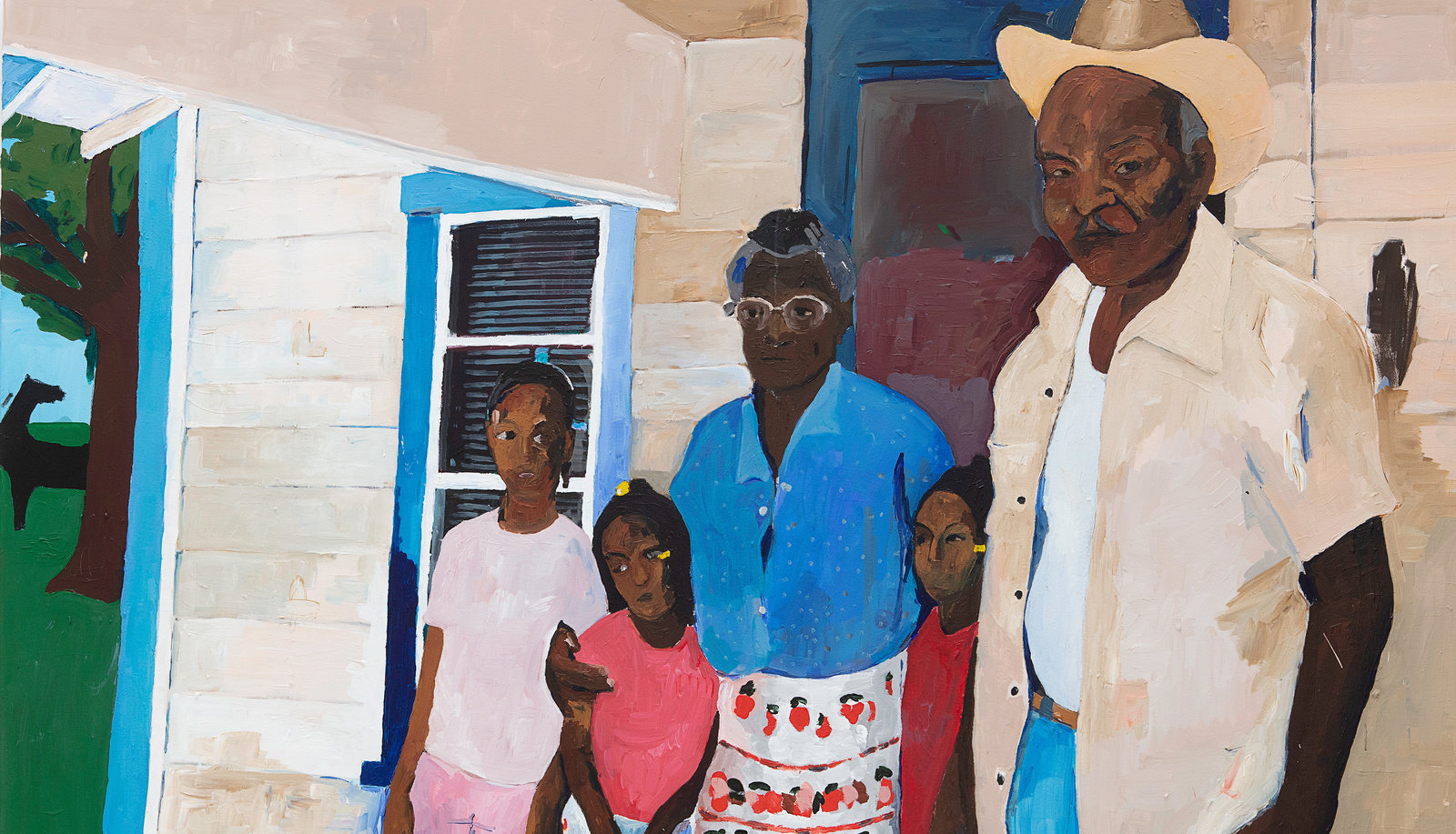

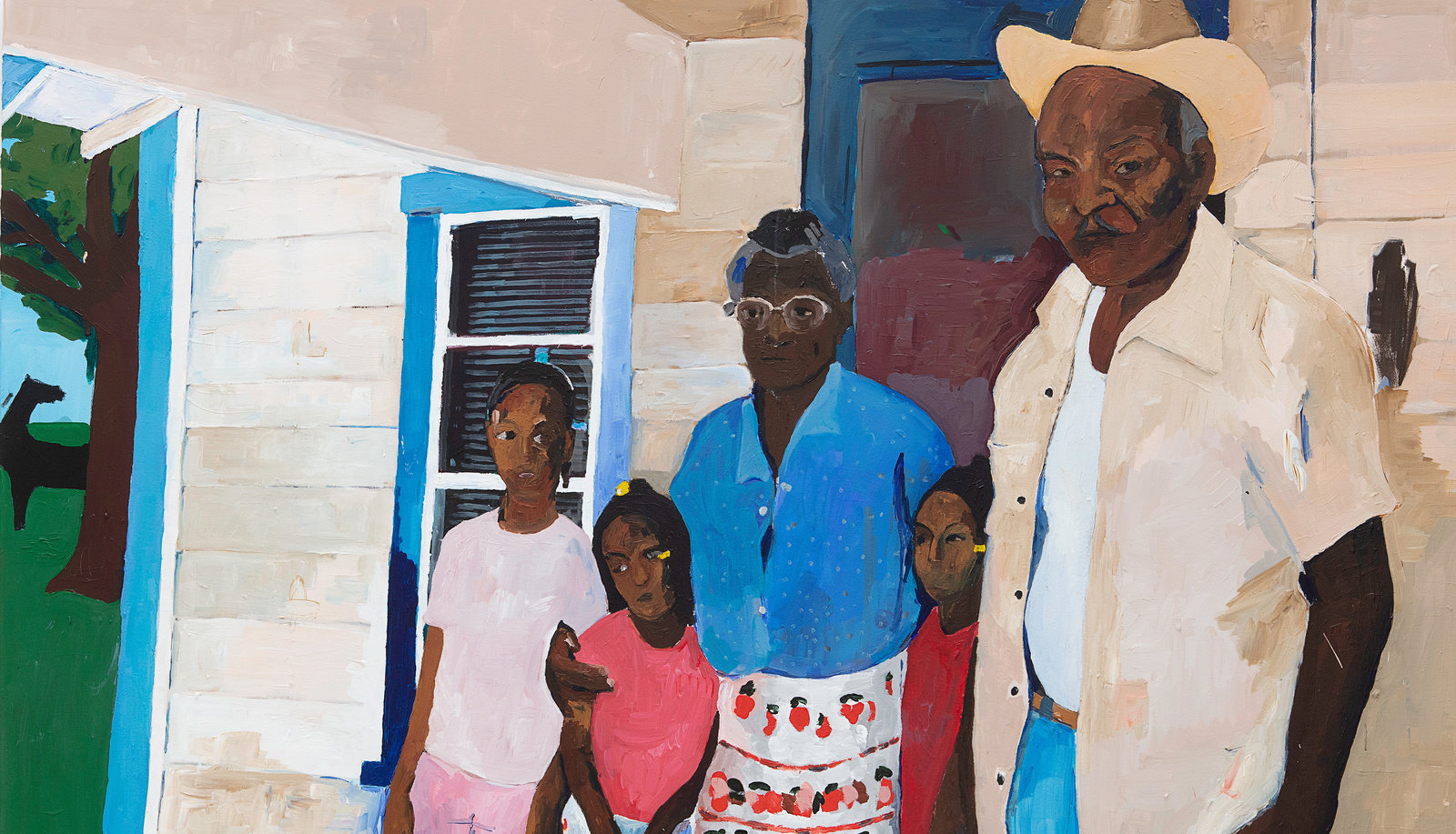

Charles: Okay, let me ask you about that. The subjects in your work seem to be ordinary people who you know or have encountered or people who you don’t know but you seem to have some connection with. Your subjects are almost always black. All of this may mean that your work is a reflection of your ordinary or lived experience, which includes relatives, friends, and strangers as well as people who’ve been culturally or economically marginalized or are living marginal existences. You may paint someone familiar to you such as a friend or a relative or you may do a portrait of a drug addict, somebody living on skid row.

Henry: Right.

Charles: I was actually interested in how you regarded those two different kinds of subjects. Are they different to you, the skid row figure and the friend or relative? What is similar about both groups that makes them part of your oeuvre?

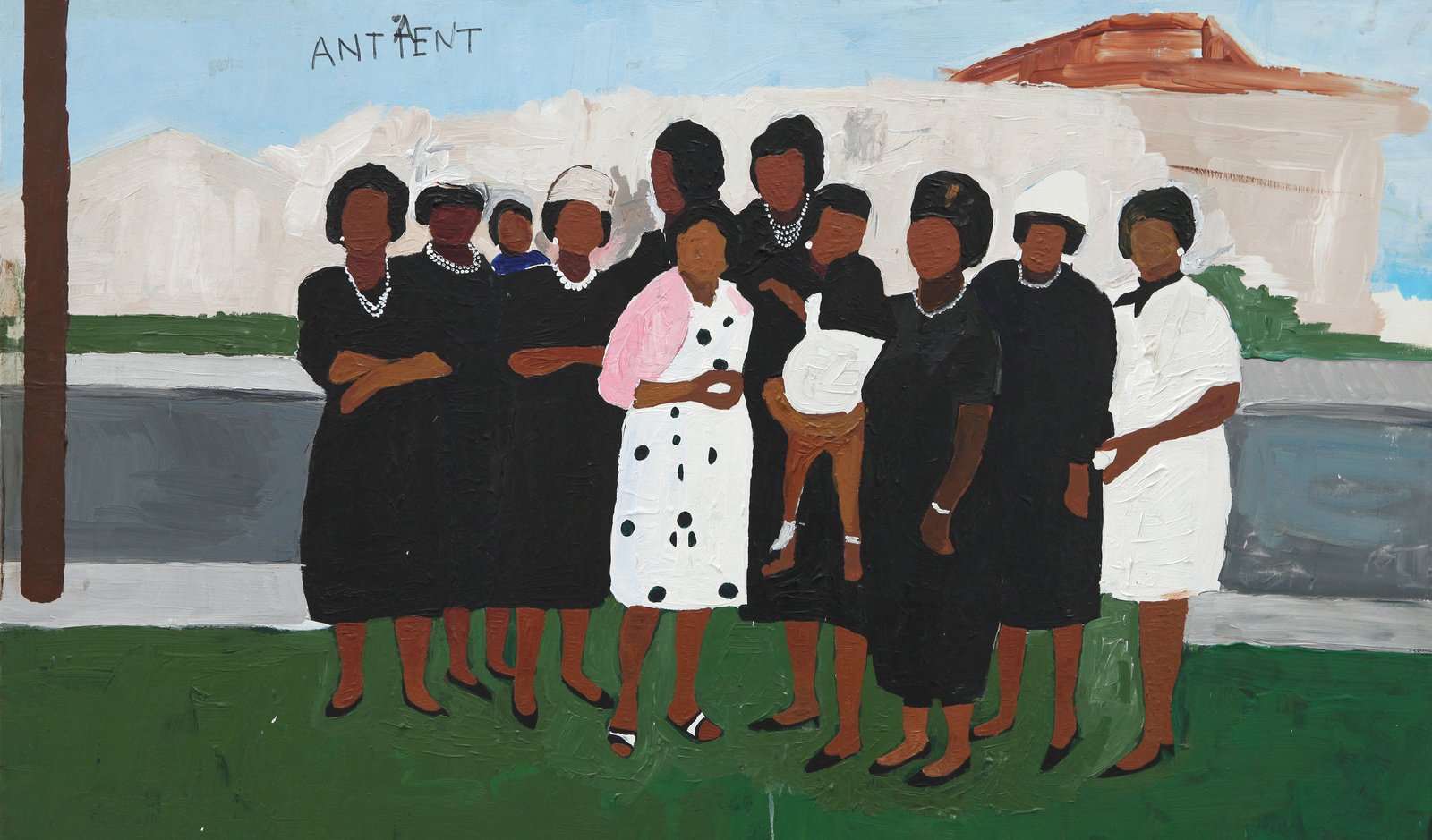

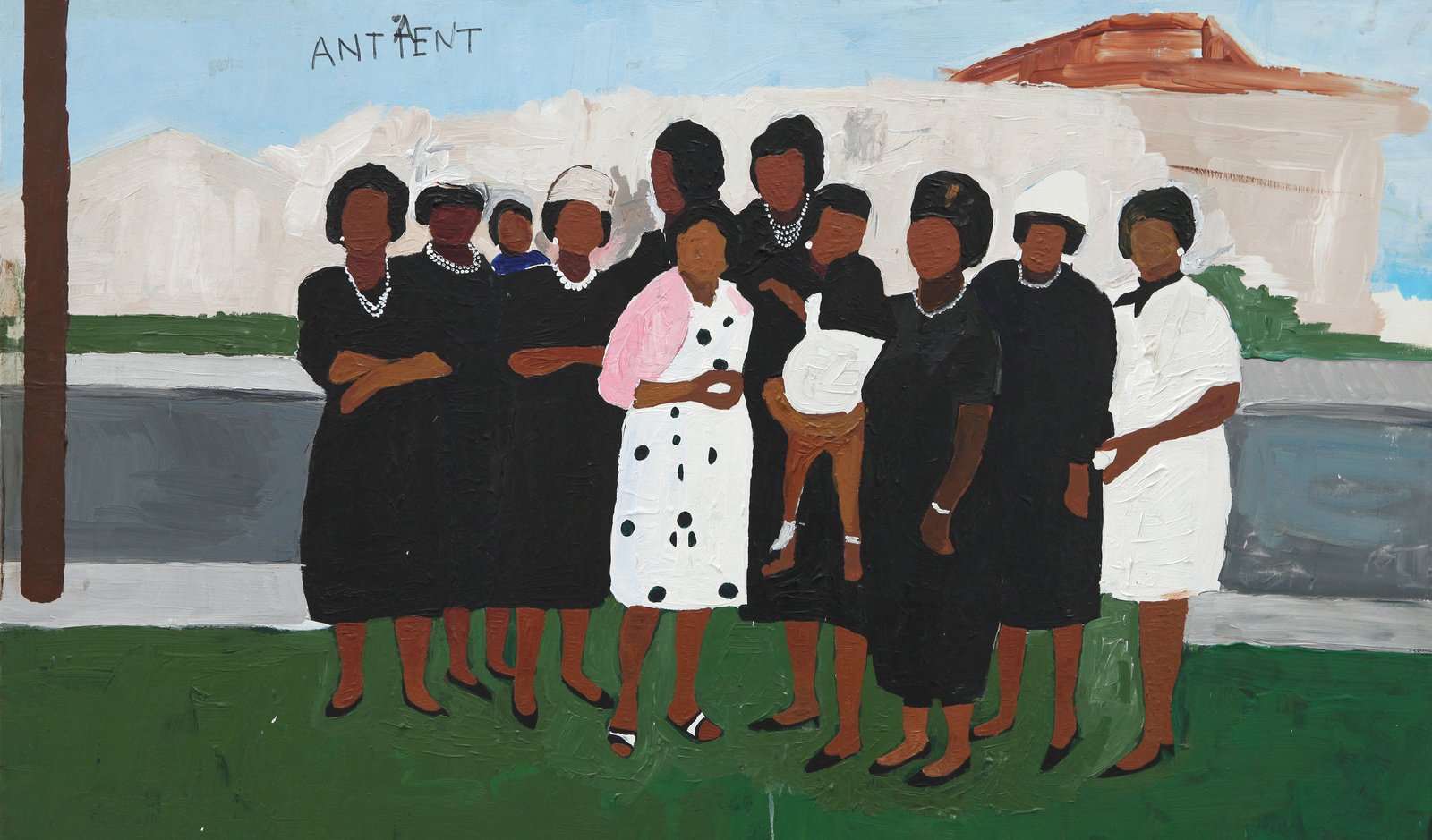

Henry: Sometimes I might paint a picture of a relative or a grandparent just because I’ve never seen their photo. The painting becomes the only visual record of their existence. Now I don’t want to say that I’m documenting even though there are some things that are more like documentation. I treat the painting like it’s a rare photograph; it has meaning beyond being a document. I never met my grandfather who was shot and killed. I have this photograph of him that I wanted to paint. It was maybe important to me just because...because it was rare. If I use a camera to photograph a person on skid row, sometimes I’d say like, “Oh wow!” There’s certain things in the image that I connect with. If it’s a relative, well of course I think it’s a little more sentimental. I was gonna say special. I might say, “This is my grandma, the lady my mom talked about who I never met.” That might provoke me to an even deeper level.

Charles: Maybe it has to do with something you said earlier about truth, that no matter what the subject is, somehow you perceive in that subject a truth that needs to be told, whether the person is a relative or a drug addict or whatever the circumstance.

Henry: What I know to be the truth.

Charles: Okay. You might be attracted to subjects that reveal a kind of truth, a story that has to be told. Does that make sense to you?

Henry: Yeah, I think it does because the truth is...but again it’s a contradiction. Sometimes you don’t know [what the truth is]. I had a cousin who I thought was just brilliant and a cousin who maybe was an alcoholic and died of cirrhosis of the liver. When you see the truth of the person, it’s gonna take you to another level. Or that woman off the street smoking crack. She did sit for me. Her truth might be that she’s somebody’s auntie or maybe a grandmother and maybe sweet as hell.

Charles: Let me know if this makes any sense: I think that the idea of truth is something that you think ennobles your subjects, makes them important. You see somebody and say, oh there is something important about that person.

Henry: Right. That’s why I say it’s my definition of truth because you’ll ponder something—question the meaning of something. I think if I didn't give certain people the benefit of the doubt or vice versa, then I wouldn’t get there. A good friend of mine, Emory, was trying to sell me watches and I said, “Man, what the fuck else can you do, these ain’t no Rolexes!”

Charles: [laughing]

Henry: But when I probe I get to the truth. I say probe because of my journalism background. My journalism teacher said, “Henry, you gotta ask the real question!”

Charles: Speaking of background, how did you come to the idea that you wanted to make art?

Henry: It’s funny because other writers have asked me this question and I come to the realization that in my answers I forget to mention certain people. I’d say it was this or that person who influenced me, but I see now that it was my father. This didn’t occur to me until at some point I needed my birth certificate, and I saw it read “Hershel Taylor, painter’s assistant.” And I realized that I’ve never talked about my father being an influence on me. My dad was an industrial painter and painted up at the Point Mugu naval base. On the weekends, he might have had a side job and I’d go with him and I would watch him paint. I remember when he died I cleaned out his apartment and I saw all these big-ass brushes and I wanted to bring them home. Also I grew up with artists. I knew the Hernandez brothers, Jaime, Gilbert, and Mario. They are famous comic book artists. Richard Hernandez, who was another brother, was in one of my classes. I also had a ceramics teacher in the seventh grade who I never forgot. We called him Mr. O. I also met with my seventh grade English, teacher who also introduced me to a lot of art. We would talk about Monet, the impressionist and expressionist painters. The first painting I ever made was at her house.

Charles: How old were you then?

Henry: Well, I was in junior high school. I used to go over to her house with the basketball team. Her husband was a coach.

Charles: You were into sports?

Henry: Yes. She would sit with me talking about art, and often with her daughter, Julie, who is a painter now.

Charles: Yet when you went to college you decided to major in journalism. It wasn’t obvious to you to be an artist?

Henry: No. When you have someone like the Hernandez brothers as a model...I always put them on a high pedestal—you think you’re not good enough. It’s like in sports. My next-door neighbor went to USC and played for the Vikings. I was a halfway decent athlete, and I hung out with him and other student athletes, but at the same time I thought I wasn’t good enough to be a player like him or any of them. The same with art. I had friends who were artists, but when I compared myself to them I thought I wasn’t good enough, not even for a scholarship.

Charles: What changed it for you?

Henry: Around 1978, I moved to Oakland and I took an etching class at Laney College. Then I moved back to Santa Barbara with my oldest brother and began carrying around a watercolor pad. And when I turned twenty-one I moved home to my mom’s house and went to Oxnard College. That’s where I took about a year of journalism. At the same time I started painting classes with James Jarvaise and worked with him for like four or five years. When I turned twenty-eight I began working at Camarillo State Mental Hospital as a nurse. I worked the swing shift so that I could still take painting classes. After a while, Jarvais said, “You gotta stop taking my class and transfer.” He recommended CalArts. Going to CalArts sealed the deal for me.

Charles: I want to return to your earlier years in Oxnard. You said your friends, the Hernandez brothers, were important to you. Was that in part because they produced socially conscious character-based comic books where sci-fi narratives played out in otherwise ordinary locations? Did their storyboards influence your interest in the human subject?

Henry: When you mentioned the Hernandez brothers, I guess so! You know, there is that saying about setting the bar high—they set my bar high. But it was mostly their drawing skills. I always thought, “Damn, they draw so much better than I.” So I started just practicing my draftsmanship because of them. They intimidated me.

Charles: Your teacher James Jarvaise was a very interesting figurative painter from the ’50s and ’60s. What did you learn from him?

Henry: When I started taking classes from Jarvaise, he would mention the names of artists to me. We only had one library so I don’t know how I would have investigated these artists without his direction. I started going to libraries and museums more frequently, picking up books on Jean Dubuffet and Cy Twombly. Twenty years later I discovered that he was in that famous exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, 16 Americans [1959]. I googled him and that all popped up, and I said, “Damn!” He really knew...

Charles: I want to deal with some of the formal aspects of your work. Your work has been described as “powerful” and “compelling.” I think that comes from a compositional style where you work in bold planar areas rather than more detailed gestures. This produces a compositional simplicity that is very powerful. I have also heard you say that you paint fast and start quickly, but then you’re a bad or slow finisher.

Henry: Sometimes I’m like a basketball team that comes out fast, pushes strong, but then can’t finish with the same intensity, something like the LA Lakers now; they haven’t learned how to finish. Sometimes I get really pumped and excited and have a good start. I’ll be pumped, and then I’ll realize like, damn, I’m not as pumped as I was. It’s like a sports game.

Charles: You have these spurts...you’ll sit back and you’ll reflect, go away, come back with broad, aggressive strokes again, and then you go away and return with broad, aggressive strokes again. You don’t slow down because you don’t allow yourself to be pinned down by little painterly gestures and nuances.

Henry: But there’ve been times when I’ll work on a painting—I’ll work on one dog for a week. It’ll be my brother’s dog and I’ll be like, damn, I can’t get this dog right. Sometimes when a gallery says, “Can we take this painting?” I’ll go, “No, it’s not done yet.” And then I won’t touch the damn thing for six months. Then I’d say, “Okay, you can take it.” I think sometimes you just have to be with work. There is work that I know that I painted and put away and forgot all about. And then somebody might say, “Why don’t you put that painting you did in the show?” And I say, “Why, I haven’t looked at it in a while.” And I’ll look at it and go, “Oh, I kind of like that.” But then I might decide to put it away.

Charles: You identify with the old-fashioned idea of the creative process—the real-time personal and subjective struggle to give reality to a painting. You identify with that struggle in the painting. But in any case, one of the consequences of this—and it directs itself to a point I want to make again later—is that your figures have a uniqueness about them because of your working process. There’s a certain similarity in them, particularly in their facial expression. More specifically in their eyes. I find an expression of innocence there. The environment around them could be anything, but their expression does not seem to respond to their environment. To me that is different from the idea that the figure is a product of or is defined by the space. Let’s say, for example, that you paint the drug addict in a certain location or neighborhood. One might read that location as tough and downtrodden, and normally that is the context for the reading of the figure. In your work, the person stands above and away from that space and it’s because of that expression, that look of innocence I see in their eyes. This puts the figure in a present moment that transcends the local specificity of the space. I think it is a characteristic I see in all your paintings that I have not really seen in the work of other figurative painters. Does this make any sense to you?

Henry: I look at a lot of figurative painters. I do separate my work from them and when I lump them together, I can’t put myself in their category.

Charles: There is a reason I bring this up—it demonstrates a uniqueness in your work. When I listen to you talk about your subjects, it seems that you’re always in that present moment with them. When you paint them, you are not in the past nor are you projecting into the future, but always in the present. You may think about the past, but you don’t go there. Somehow you are able to get that moment in the figure.

Henry: Definitely a different energy.

Charles: Most of the commentary around your work points to a boldness of style and a talent as a colorist, also the rapidity and speed of your execution. This to me makes you look like the kind of artist that’s acting more than thinking. Totally intuitive.

Henry: Right.

Charles: But I think this is an oversimplification of your process. It’s true that you are spontaneous, but you’re also very conscious and reflective, in the present moment. Operating in the present moment must produce a different type of reflection. Your present moment is more than just the space of intuition, it is an intellectually reflective experience. Am I off base?

Henry: For example, I did this painting. [drawing a sketch of the painting] It has Ronald McDonald here, it has soldiers here, and it has my mom’s house there.

Charles: Is that the painting where you stole a Ronald McDonald figure?

Henry: No, this scene is in Thailand. I began to read into the images at that time. Thailand means “City of Peace.” So when I went to Thailand all I could think about was my brothers who went to Vietnam. I thought about other things when I was doing this painting. When I went to Oxnard, there was a cleaners where I used to work. A Mexican guy worked there, and he said to me, “Are you Hershel’s brother?” That was my brother who got shot at twenty-two on his birthday. Earlier, when I was young, around eight, nine, ten, I read all my letters from Hershel to my mother, many times, over and over again. And I used to copy his handwriting. I also think about my brother Gino, who was a tunnel rat but now a minister with a doctorate in religion, and I asked him what music he listened to when he was in Vietnam. He told me Little Richard. So I wrote that down, but all I could think about in this moment were soldiers. I think about all this in this painting. It’s still in my studio and it’s thirteen feet high. So yeah, I think about my work for a long time. When I execute it, I do it real fast but I’ve thought about it a long time. For me, this painting was a work that took thirty years.

Charles: But...in the moment of execution you brought the whole past to the present.

Henry: Yes. Sometimes it’s a narrative of my past or I construct the narrative. It depends. If I am having an exhibition this might also affect things. I might have three paintings where I’m working through this narrative.

Charles: What’s the name of that painting?

Henry: I forget. [Author’s note: The painting is Untitled (2012–13).]

Charles: There is indeed a lot that goes on in the work. It didn’t just suddenly happen; it’s a result of reflection and thought. Your strength is that you’re able to take that expanded period of thought and make it an instant in the painting.

Henry: You hit it right on the head. You’re absolutely right. That was the approach I had recently when T Magazine called me and said, “Hey, Henry! Would you do two paintings for T Magazine?” I could have said, “I’m not doing no T,” but I said, “Wow.” It just sounded good in that moment. Right after that I get a call: “Henry, T Magazine wants you to do a portrait of Jay-Z.” So I thought I only had to do one. And they said I could keep it. That was enough incentive for me, so I said, “Yeah, I could do that.” Sometime later the gallery called me: “Henry, you got the painting?” And I said, “Hell no, I don’t have it.” Right after the proposal I traveled to Madrid for a friend’s funeral. I was there for a week—I wasn’t thinking about the deadline. When I got there I only had my cell phone. I didn’t bring a laptop. So on the phone I started my research. I was looking for an approach. Something different. I thought about a lot of different painters and a lot of different approaches of how I wanted to do this painting. I looked up Picasso because I started to think about cubism. That was because I thought about Jay-Z’s lyrics. I must have started three or four portraits. I put a lot of thought into things, then it’s like, out the window.

Charles: Out the window. What does that mean?

Henry: It mean, I can’t just sit here...

Charles: You don’t want to stay locked into the research on your subject.

Henry: If I stay locked in it, I won’t finish. Henry has to come in here too.

Charles: For me, that’s all Henry. It’s the way you make work. I want to ask you what you think of people who describe your work as “intuitive” and “raw.” My late friend Terry Adkins hated that, because they used to say that’s the way he made his work. He didn’t want to reinforce the idea that black artists weren’t intelligent.

Henry: Yeah. And sometimes you might be having a Modigliani moment. I think about a lot of things. It’s not like you don’t know when a certain history is going to appear. I was doing this painting and I was thinking about a work by another painter. I said, “I’m gonna borrow that.”

Charles: I’d like to talk about something slightly different: your work and its relation to politics. You were asked in an interview what you thought about politics and art. You said that if you’re a black artist, there’s no way in the world that you can function outside of politics. It’s just what happens to the marginal subject in this culture. But my question is, how does your work deal with the political since it doesn’t seem that you are a political artist. You did a painting of the Philando Castile shooting that was shown at the last Whitney Biennial. The painting takes on the specific event of this shooting. But it also represents the larger narrative of the history of cops murdering innocent black men. As you know Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till’s body lying in a casket was also in that show [Open Casket (2016)]. When I think of the way you deal with your subjects—that they exist in the present—your painting is then about the terrible moment that Castile’s life ended. But this can also be read as a critique of the persistent racism that exist in police departments. Since your paintings are about your experiences and the people who occupy them, politics does not seem to be your primary interest, especially since there are sometimes white subjects in your work. This reinforces that you paint from your immediate experiences. But the Castile painting illustrates what you meant when you said if you’re a black artist your work will be political; it goes beyond an experience because Castile also represents the history of cops shooting black men.

Henry: Sometimes we’re just horrified by a lot of different things. Let me know if I’m going too far off track, but we talked about my time studying journalism. Mark Dever was my journalism teacher, and he always said it was all about the first paragraph. But it was also about the larger practice of journalism. We were taught to look into the story for the who, the what, the when, and the how. And so I got in the habit of doing that. It is a slight obsession when I read newspapers. Like, turning every fucking page. I know that there is always deeper content. And now this is part of my passion for painting. You can’t separate yourself from your subjects because you internalize so much. I can now remember things that I researched in the pages of newspapers for years afterwards. And sometimes I paint about them. Maybe I became a Bob Dylan fan after reading about [Black Panther leader] George Jackson—fucking Bob Dylan singing, “Oh, they shot George Jackson.” I remember hearing the song in an alley when I was fifteen years old. That’s how I know about Hurricane Carter, and I know about Hattie Carroll because William Zantzinger killed Hattie Carroll. So that’s how politics segues into my work. It has to do with finding things that horrify me in the newspaper..

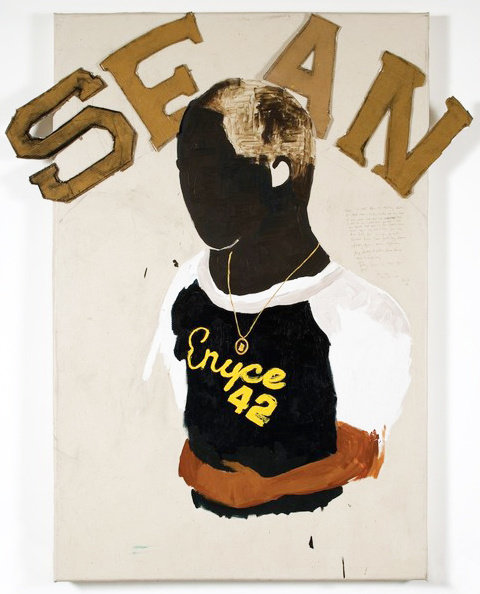

I know sometimes it’s a fucking reaction. Like when you see something wrong and say, “Fuck, stop that.” I remember the Sean Bell shooting. I did a painting about it for Sis and Bra, my show at the Studio Museum in Harlem [Homage to a Brother (2007)]. I read about Sean Bell because like him, I like baseball, and I’m like, “Damn, that brother sounded just like me!” It could have been me. He was just a happy kid, I could picture him out with his friends...So I made that painting that morning, right after reading the article.

Charles: If we can shift ground again, although it is not really unrelated to what we were just talking about, I spoke earlier about the way you treat the figure. When looking at your paintings, suddenly we find ourselves in this present moment, the moment of the now with respect to the figure. There is this look of innocence that I mostly read in the expression and countenance of your figure. This seems to make the figure unique and special. Laura Hoptman criticized what she found to be a standard in painting black people, that the black subjects are mostly exceptional people. She suggests that when you reinforce the idea of the individual by painting only the exceptional, you separate the individual from the community. So in history, when black people were painted by black artists, it was because they were special and not regular or ordinary folks. In your work you individualize your subjects, but they remain normal people. Maybe it’s this expression of innocence, this countenance that makes the normal person exceptional in your work. They are individualized without becoming separated from their community. It can be said that you present a new idea about how the black figure should be treated. For me this is a political construction.

Henry: I had a brother who was a straight-A student and ASB [Associated Student Body] president. His name is Randy. Ultimately he went to the University of San Diego to study to be a veterinarian. Then one day his girlfriend suddenly died in a car accident and he was never the same. I had to identify her body. Here’s this brother who I had always looked up to, who I still look up to. But now he’s living off the grid in east Texas with wolfhounds and mastiffs. He met Cesar Chavez at a young age and was acquainted with Angela Davis. He started a Black Panther chapter in Ventura County because we used to go Oakland and hang out with them. Now he’s living off the grid.

Charles: Isn’t this about finding the truth in people that makes them exceptional, but not in the Hoptman sense? Like your brother?

Henry: But he doesn’t look exceptional.

Charles: Right, it’s not because he’s black that he is exceptional. He’s black. But you are finding what’s exceptional in the regular person, and sometimes it’s something dystopic.

Henry: Maybe it’s Randy who helps facilitate this idea.

Charles: Can we go back for a moment to the Whitney Biennial and your painting? You’re probably sick and tired of talking about this issue. But I noticed that Dana Schutz’s painting was responded to differently than your Castile painting. She was castigated and you were not. Why do you think that happened?

Henry: We’ve taken PC to a whole another level. I just read about Sam...

Charles: Sam Durant’s work Scaffold (2012) at the Walker Art Center?

Henry: Yes. What I take from this is that I don’t really want to be censored.

Charles: But you weren’t censored. She was, so to speak. Why do you think people didn’t boycott your painting?

Henry: I’ve asked myself that. I don’t know. Because I can have empathy and so can she. Or maybe it’s not empathy but righteousness. What would a more sincere response be? I don’t know who owns the subject of violence against blacks. I can only speak to how I approach a subject.

Charles: Do you want to know why I think it happened? A couple of things. Some people have the opinion that you as a black person have the license to paint about black people and she doesn’t. I don’t buy that, but in this case it is about how differently each of you treated the subject. She used a subject that had become part of the political narrative on racism because of what Emmett Till’s death represents, but so did you with respect to Castile. You treated a similar subject differently. I had mentioned earlier what you do that’s unique, and it is because you individualize the person from the context without completely separating them. The storyboard narrative is there, but the person seems to exist as an individual in that narrative. The opposite, or a different way, this can work is that the individual can represent the narrative. In this case the subject is interpreted in terms of the narrative and only in terms of the narrative. In Dana’s painting, Emmett Till becomes an example of violence and he is only meaningful to her in terms of how he represents that violence. But for you, Castile is not just an example of violence. He is an individual who exists within the space of violence. That’s what I think is different. Two ways of dealing with the political narrative. You have any thoughts on that?

Henry: First of all, I’m immersed in these types of experiences every day. That doesn’t give me a license necessarily but there is a difference. For her it’s sometime-y, but I have lived with that violence, and still do. At the same time I just hate to see anybody get the beat down. I do have empathy for her, but I also get why it’s a problem for some.

Charles: Thank you, Henry for this very compelling conversation.

Henry: My pleasure, Charles.