Blum & Poe Broadcasts presents free and public access to scholarship and writerly ponderings from our publications archives and network.

In focus this week—an essay by Lowery Stokes Sims from Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2019). This book is the most comprehensive volume devoted to the life and work of pioneering African American artist Robert Colescott, accompanying the largest traveling exhibition of his work ever mounted. This volume surveys the entirety of Colescott's body of work, with contributions by more than ten curators and writers, and features reminiscences and thought pieces by a variety of family, friends, students, curators, dealers, and scholars on his work as well as a selection of writings by the artist himself.

Colescott in the 1980s and '90s: Stranger in a Strange Land

By: Lowery Stokes Sims

In the 2017 exhibition Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s, organized from the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, curators Jane Panetta and Melissa Lang installed the work of Robert Colescott alongside that of David Salle, Sherrie Levine, and Julian Schnabel. Amid the relatively slick surfaces and disjointed spatial elements in the compositions of these artists, the aggressively gestural painting and allegorical quality of Colescott’s 1981 The Three Graces: Art, Sex, and Death (now in the collection of the Whitney Museum of Art) stood out like the proverbial sore thumb. Even juxtaposed with the more expressionistic work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, the fleshy surfaces of Eric Fischl, or Leon Golub’s “scraped-down, ever-shifting layers of dark and light,” [1] Colescott’s lumpy funkiness and bright colors demonstrated the distinctiveness of his work within the art decade that he helped define. Never mind the fact that he was in his fifties, a generation older than most of the artists he was exhibited with at the Whitney.

It was Colescott’s predilection for parody and satire and his inclination toward side-winding polemics about race, gender, and their actualization in history and contemporary life that established his relevance with the emerging generation of artists in the 1970s and ’80s. His irreverent disruptions of artistic hierarchies, stylistic protocols, and social proprieties established Colescott as one of the “bad boys” of the art world at a moment when that world had liberated itself from the tyranny of formalism. As seen in exhibitions such as the 1978 Art About Art, organized at the Whitney Museum of American Art by Richard Marshall and Jean Lipman, and the 1981 exhibition Not Just for Laughs: The Art of Subversion, organized by Marcia Tucker at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, the art of the decade precipitated a reconsideration of “the traditions of figuration and history painting,” a discovery of “new interpretations of abstraction,” an attempt to address “fundamental questions about artmaking.” [2] More pertinently, they also “took on political issues including AIDS, feminism, gentrification, and war.” [3] Add race and you have a laundry list fit for Colescott.

As we read in Matthew Weseley’s essay “Robert Colescott: The Untold Story” in this volume (pp. 12–41), Colescott had a head start on his younger cohorts. By the time the art world caught up with him, he had taken his blackening of well-known art historical masterpieces to what might be considered the limits of appropriateness in his efforts to upend media messages. In fact, it might be said that he was in danger of being caught in a one-note habit that initially cemented his artistic brand, but ultimately would limit and date his visual enterprise. As we shall see, in the 1980s and ’90s he found new ways to tweak bourgeois pretentions through the lenses of race, gender, and class.

At the same time that Colescott’s profile in the art world rose, he entered the vaunted realm of “master”—albeit a rogue one. In 1985, after teaching at the San Francisco Art Institute for seven years, he was recruited to be a Professor of Art at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Moira Geoffrion, who had become head of the art department that year, revealed that this was a moment when the university administration was seeking to diversify the faculty in terms of race and gender in order to enhance the reputation of the institution nationally. [4] Since Colescott had already established his place in the art world, he brought a specific attitude and resources to Tucson, and fortuitously his move to the university there saw his work evolve into a new sphere of complexity and technical virtuosity. He was appointed Regents Professor of Art at the university in 1990, five years before he retired in 1995. During his Tucson period, he was in demand as a lecturer and artist-in-residence, and received a number of awards, grants, and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1980 and 1983 (having received his first in 1967), the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in 1985, and the Marie Walsh Sharpe Foundation in 1991. He also participated in the Roswell Artist-in-Residence Foundation in 1987 and was a resident in lithography at the Tamarind Institute in 1989. On a personal level, having divorced his third (and fourth) wife, Susan Ables (whom he had divorced and then remarried in 1979), after the birth of their son, Daniel, in 1980, he began a relationship with one of his students, Colleen Hench. They would marry in 1986 after he moved to Tucson; their son, Cooper, was born that same year.

Although he found recognition on the East Coast in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Colescott actually found his signature style in the context of the funky, expressionist art scene on the West Coast that included artists such as Joan Brown, Manuel Neri, Robert Arneson, Roy de Forest, William Wiley, cartoonist R. Crumb, and H. C. Westermann. Therefore it is not surprising to see in works such as The Three Graces: Art, Sex, and Death that Colescott in the 1980s revisits the more gestural and textured surfaces that declared his roots in Bay Area Figuration in the 1950s and ’60s, in contrast to the relatively flat, poster-like approach to form in his paintings of the 1970s. [5] All these developments in Colescott’s artistic evolution allow us an opportunity to consider his work beyond the familiar focus on his role as a “joker” or the “court jester of black art.” [6] We are inevitably led to recognize his deep commitment to studio practice, which he felt was ignored by art historians, curators, and critics, who focused on deciphering the stories in his art at the expense of analyzing how he painted them. [7]

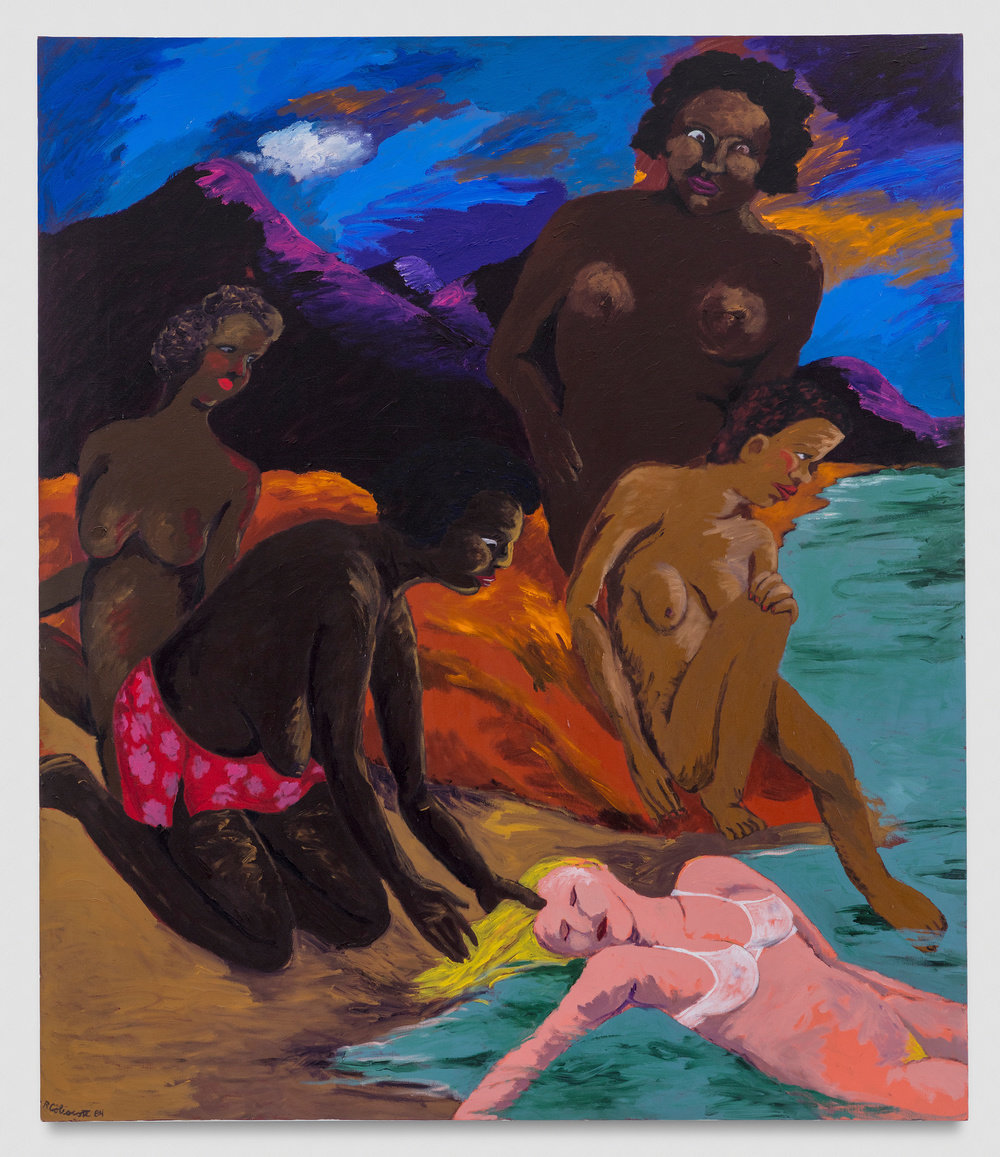

The painterly touch of Colescott’s work of the 1950s and ’60s is evident in the series of images he produced on the theme of bathers in 1984–85. While he had always been captivated by the female form, through the theme of the bathers, Colescott engaged tropes of the exotic in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that had been fueled by the escapist fantasies of artists such as Paul Gauguin. Colescott noted in 1997 regarding this series:

I thought a lot about Cézanne’s bathers and Matisse’s bathers, and thought I would do some bathers. They’re about competing standards of beauty, and also about the intrusion of the white world on a black world. It also poses the idea of a beauty parade. And it refers to the Demoiselles d’Avignon. [8]

So while Colescott continued to explore his well-established strategy of appropriating well-known themes from European art history, he became more involved in both the symbolic approach and the sensuousness of historical French painting:

The subject matter has more a poetic sense…though it still generates thought about identity and makes a social statement. But the narratives are less clear, and there’s [a] psychological statement to each one. [9]

He was also very conscious of the relationship of his work to what is called the grand tradition in art history:

I’ve had women ask me when I’m lecturing, “Why did you make [your female figure] naked?” My answer is, because I’m painting in the grand tradition. The Egyptians painted nude women. African art is almost entirely nude women. And it’s the grand tradition in Western art that I’m part of. [10]

The Bather series presents a progression of interracial encounters in some fictive Edenic locale. In what is presumably the first scene in this story, Gift of the Sea (1984), an unconscious white, blonde woman is washed up onshore. A group of black and brown women look on as one reaches out and touches her. They are completely nude except for the figure on the left, who wears a colorful short garment around her hips. [11] The white woman has lost all her clothing except her brassiere. [12] While we assume we know what has happened, the painting raises a number of questions: What is really going on? Where are we? Who are those black and brown women? Who is the white woman? Where did she come from?

While the appearance of this woman alludes to the story of the Birth of Venus, in the successive paintings in the series it is clear that Colescott’s conceives her as a deus ex machina in a narrative that deals with an identity crisis that her arrival precipitates among the black population of Colescott’s fictional Eden. In At the Bather’s Pool: Apparition of Venus (1984) the black woman at the forefront looks down into the pool and sees herself reflected back as the blonde woman. The white woman therefore symbolizes the disruption of the status quo by the political, social, and economic forces of invading, colonizing forces. In the realm of race and gender, she also recalibrates criteria for acceptance and admiration for the female figure on the global artistic stage. The tropes of beauty and the gaze are also evident in other compositions, such as Laureate at the Bather’s Pool (1984). Here black women prance and preen in front of a white male poet who sports a laurel wreath and appreciatively observes the scene. Significantly, a white woman is nowhere to be seen. Some kind of equilibrium is restored to the self-regard of the black women, but we know it is in terms of “another judgment.”

© Robert Colescott Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

© Robert Colescott Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

That idea of alternity informs the title of Big Bathers: Another Judgment (1984), where, in a departure from the usual versions of the Greek myth of the Judgment of Paris, Colescott depicts four rather than three women of different racial mixtures, features, hair textures, and body proportions, celebrating diverse modes of beauty according to a different criterion or judgment. Colescott does not hesitate to implicate himself in this societal conundrum and capture his own existential contradictions. Unmistakably identified by his mop of white hair and mustache, Colescott is seen lounging indolently at the lower left while the women, standing in a wading pool, engage in a competitive face-off for his evaluation. The prototype for this composition and subject matter can be found in Lucas Cranach the Elder’s c. 1528 The Judgment of Paris. His lackadaisical posture mimics that of the indolent Trojan prince Paris—who has been deputized by the god Zeus to choose the most beautiful among the three beauties before him. (It is not incidental that as a reward for picking the candidate supported by Hera, Paris is able to seduce and kidnap Helen of Sparta, wife of Agamemnon, as the opening parlay in the Trojan War.) The prized golden apple lies on the ground near the artist. But do not be mistaken: the quartet of multiracial women in Big Bathers: Another Judgment does not constitute an emerging sisterhood even in the face of a common confrontation: male dominance. Nor had Colescott completely purged himself of his own preferences and obsessions.

As Weseley has outlined in his essay, Colescott was a light-skinned black man who for much of the first half of his life either passed for white or evaded any question about his racial identity. He was married to four white women—one he married twice—before he married an African American woman at the end of his life. In many of his compositions after the 1970s, he was involved in a prolonged and complicated process of self-identification and self-positioning in the intense racial drama that has marked the history of the United States. We can see this in his self-portrait as a Peeping Tom furtively looking through a basement window in the 1980 Susanna and the Elders (Novelty Hotel), where a drastic retooling of the biblical story is unfolding with a flirtatious and seductive Susanna, or in his tentative posture in Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder (1979), whereas the painter at his easel he turns uncertainly to greet his voluptuous white, blonde female model, who is removing her clothes. He discussed this painting with artist Joe Lewis in 1981, noting “I [was] involved with these non-flesh-and-blood women that are made of paint and canvas. While painting these dancers as Matisse, I’m also faced with this flesh-and-blood woman. It’s a conflict between art and reality.” [13] Not parenthetically, we might note that he pursued his personal life and dealt with such subject matter at a time when mixed-race marriages were illegal in a number of states in America, so by leaving his racial identity nebulous he was able to escape certain social probation. [14]

Colescott brings his examination of alternate aesthetics to Laureate at the Bather’s Pool, where the central female figure has been painted with jutting breasts and a lithe physique and segmented joints that are reminiscent of African sculpture. Colescott presents these standards of beauty and female body proportion even more specifically in At the Bather’s Pool: Interracial Blues (1984). The black woman at the center of the composition is depicted with gourd-like breasts and a barrel torso that invites comparisons with African masking traditions that celebrate pregnancy among the Makonde people of Tanzania, for example. While Colescott dives in headfirst to deal with the fascination with figuration in the art of Africa, the Pacific and pre-Columbian America that precipitated the development of European modernism, this appropriation is not just a reversal of Picasso’s African appropriations but a direct quotation from African art, again providing a model of “another judgment.”

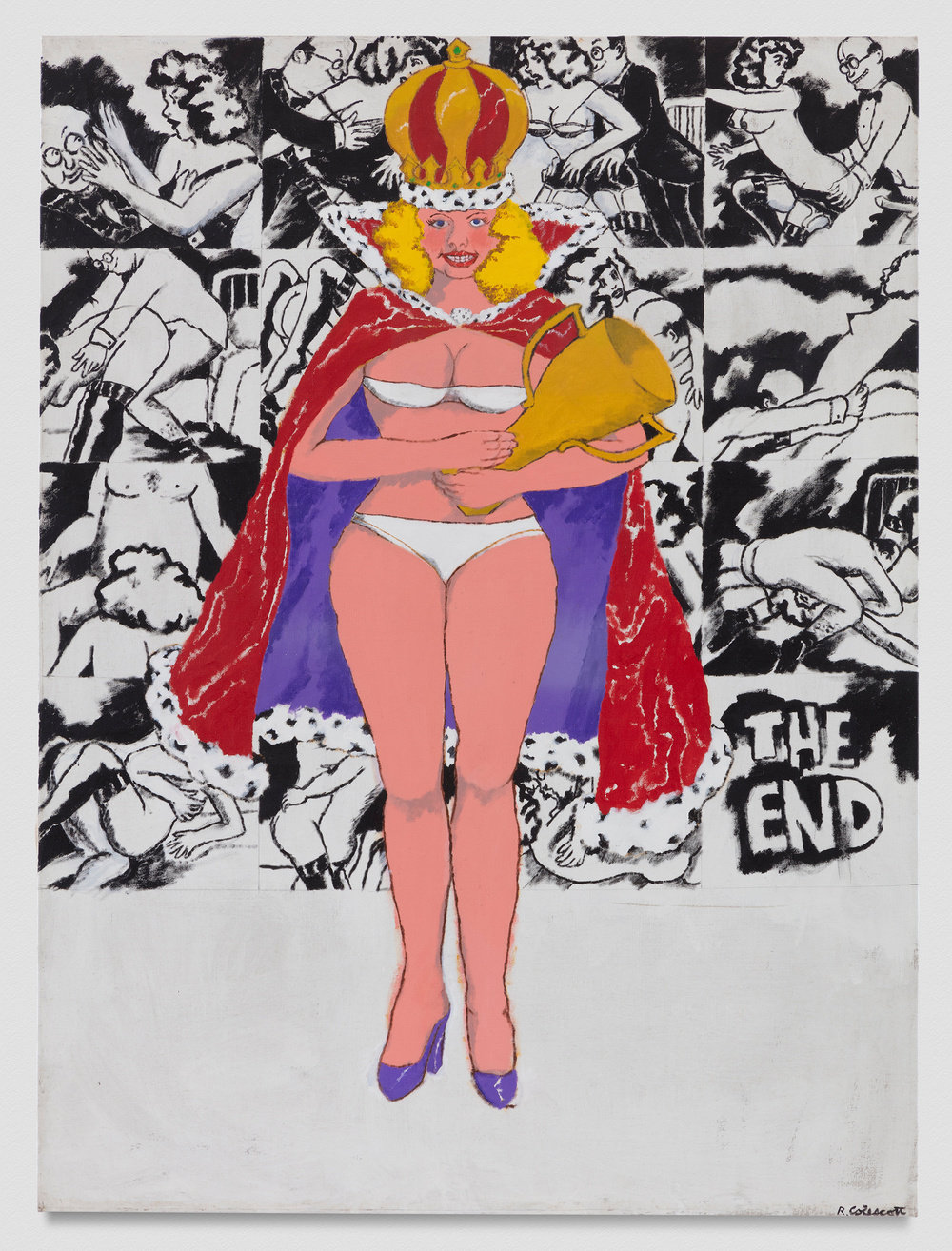

At the same time—almost as a counterpoint to these formal experiments—Colescott references the pinup girls and Hollywood goddesses of the 1940s and ’50s in the figure of the blonde woman in the Bather series, with her ample proportions and hairstyle of the period. They also populate such 1970s paintings such as Bye, Bye Miss American Pie (1971), Café au Lait au Lit (1974), A Winning Combination (1974), American Beauty (1976), and even The Three Graces: Art, Sex, and Death. These female types demonstrate how, for Colescott, an anti-academic, iconoclastic approach to figuration and oppositional prototypes of exoticism, sexuality, and even vitality are not exclusive to one race. In 1995, he notes that people wondered why he made his women “ugly, fat, and lumpy,” observing that:

There are other societies in which “fat” is considered beautiful. At different times we, as the human race, have had different images of women and men. In Paleolithic times the female archetype was made up mostly of genitals, buttocks, and breasts—it was an ideal that had a lot to do with fertility and reproduction. [15]

Colescott’s reappropriation of the “classical” female body, therefore, returns it not back to academic classicism, but forward, effectively “creating a type”—to borrow a phrase from Kenneth Clark [16]—that combines various anticlassical tendencies: even transposing them on individual female figures—white, black, or mixed race.

The black woman in the Bathers does not achieve total autonomy outside dominant and persistent societal hierarchies until the 1985 work At the Bather’s Pool: Ancient Goddess and the Contest for Classic Purity. The composition is presided over by a black woman with long, kinky/curly red hair. She is “Venus Naturalis,” the sensuous, earthbound mother of all mankind. [17] Colescott positions her not only to challenge but to co-opt the classical Greek ideal and, like her predecessors in the 1970s, engages the viewer through the penetrating gaze of her literally blank eyes. This forestalls any wink-and-nudge sense of complicity that might have been shared with the viewer. The ancient goddess is the antecedent of the central figure in an earlier composition from 1983, Mother Nature (African Venus), in which the black woman wears the shell of Venus as pasties. As she stands on a globe and is surrounded by the cornucopia of the earth, she melds with the persona of the Roman goddess Fortuna. [18]

Perhaps the generative role of the goddess in the 1985 painting is indicated by the formation of pink clouds dissipating behind her head that remotely suggest the orb and double phalanges of the headdress of the Egyptian goddess Hathar, who presides over love, motherhood, avatar of the Milky Way and the night sky. This can be seen as a nostalgic look back to Colescott’s Valley Queen paintings of the late 1960s (such as Nubian Queen, 1966), which he painted during his time in Cairo between 1964 and 1967. As Colescott noted, these meditations on color and form represented “the spirit of [the] dead queens” that he discerned “ in the surrounding rocks and crevices.” [19] Indeed, in the presence of the wall paintings in the tomb of Queen Hatshepsut (at Deir el-Bahari, on the west bank of the Nile near the Valley of the Kings) that cosmic energy is palpable to this day.

The 1980s is also when Colescott entertained more personal subject matter in his work. In particular his marital and romantic relationships are evident as seen in The Judgment of Paris (1984) where Colleen Hench is the redhead seducing the artist in front of the other women who are rivals for Colescott’s affections. In Jealousy (1984) Colescott and Hench are seen floating on a cloud/cushion that is held aloft by a female figure in a black evening dress (personifying the emotion) over a landscape strewn with discarded bits of warfare that indicate a turbulent relationship. In Down in the Dumps (So Long Sweetheart) (1983), we see the artist sitting on the edge of a pile of jettisoned objects as Hench marches away. We see only her red hair, bare back, bottom, and high heels as she exits the composition. This is clearly a man in the throes of a romantic entanglement, who momentarily abdicates his power position within the rubric of the male gaze by daring to bear his own haplessness in the presence of his romantic obsession. Therefore, the subject of the Judgment of Paris intersected with the Bather paintings to create a new narrative that conferred power to the female figures. They were not only subjects of the gaze but also controllers of the gaze who determine how they might be gazed upon.

© Robert Colescott Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

© Robert Colescott Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Colescott brought the conversation about female agency back to its most notorious example when he painted two riffs on Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). The two Les Demoiselles d’Alabama paintings of 1985 feature the figures nude in Les Demoiselles d’Alabama: Desnudas—but rendered in Colescott’s characteristically fleshy, gestural style that contrasts with Picasso’s more linear, graphic style—and dressed in exuber-ant 1980s-style fashion in Les Demoiselles d’Alabama: Vestidas. He explained that these paintings were “about sources and ends,” and he positioned his work at an antipode to that of Picasso, who “started with European art and abstracted through African art, producing ‘Africanism,’ but keeping one foot in European art.” Colescott, on the other hand, “began with Picasso’s ‘Africanism’ and moved toward European art, keeping one foot in ‘Africanism.’” [20] The women in Les Demoiselles d’Alabama are just as sassy and confident as the ones in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, directly confronting the viewer. This appropriation not only destabilizes the male gaze, but also the presumptions of standards of beauty, which were more fully explored in the Bather series. All of this is contextualized in psychological, social, and aesthetic consciousness on the part of women of color, during the halcyon era of “Black is Beautiful” in the 1960s and ’70s.

These ideas unexpectedly became the subject of the collaboration between Colescott and Carrie Mae Weems, who was asked to make a portrait of the artist for the catalogue accompanying Colescott’s exhibition at the United States pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1997. But Weems had other ideas:

I thought that as opposed to trying to figure out how to make really a work about Bob specifically, it might be more interesting to make a work around the work that I make, which is based on the critical intersection between art and practice, men and women, and gender and identity, and notions about the object and the subject. Sort of bringing all of those ideas to bear on posing myself in relationship to Bob. [21]

The resulting image, Framed by Modernism (1996), is a gelatin silver print triptych that depicts a nude Weems standing in various poses in a corner at the back of Colescott’s studio. Colescott himself is seen in the foreground of the studio space, standing next to an easel with his head in his hand in one frame and on his hip in another.

The arrangement is similar to that of Velázquez’s Las Meninas: as the artist looks out toward the viewer, and with Weems sequestered in the background, the relative roles of the artist, model, and viewer are in question. But in truth it is Weems who, despite her diminutive presence, is in control of the situation. As she noted:

[There is] this sort of deep looking at one another, even as we’re looking at his painting. And he is looking at me as the subject and a maker, and my critical gaze at his painting and at himself. So I think it kind of works in this circular way. You keep coming back to a level of conversation, of dialogue that brings us in and out of painting in fascinating ways. And I think that the work is sort of exceptional. [22]

So Weems seizes a sense of her own agency by noting that both she and Colescott are equally “FRAMED BY MODERNISM” as they framed each other. The captions accompanying the images, acknowledge that Weems and Colescott have been “SEDUCED BY ONE ANOTHER, YET BOUND BY CERTAIN SOCIAL CONVENTIONS,” nevertheless “EVEN THOUGH WE KNEW BETTER, WE CONTINUED THAT TIME HONORED TRADITION OF THE ARTIST & HIS MODEL.”

As noted above, by the 1980s Colescott’s painting demonstrates an engagement with a more activated, morphological approach to paint. Particularly in the period 1984–89, his surface treatment and paint application increasingly came to complement the narrative in these works. [23] In Knowledge of the Past is the Key to the Future: Upside Down Jesus and the Politics of Survival (1987), one in a series of compositions examining the presumptions of race, gender and history, Colescott scumbles different and oppositional hues into the main color of each figure: darker areas into the beige-y pinks, umbers into the browns and dark browns. On the one hand, this can be seen as a chromatic device to convey modeling in a less simplistic or graphic technique, taking into account the effect of light on the surface of various skin colors. But it also becomes a vehicle for Colescott to literally intermix the “Other”—black and white—into each figure. As Colescott himself also noted

We always think of [Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa} as being very separate. Yet they merge…In different kinds of people, and the mixture of races, [the region] becomes less a place that’s either black or white. In my interpretation of women—black women with blonde hair, women with African features—there may be more of a sense of the real identity of the black “race” in dealing with a larger issue of identity. Who are the black people? And who are these black women? It reflects a historical relationship between black and white in terms of race. The closer you are to Africa, the darker the people are in southern Europe. The closer North Africa is to Europe, the more European the people appear. So there is this blending of race that is a true reality.’” [24]

In Knowledge of the Past is the Key to the Future: St. Sebastian (1986), the scumbling technique is even more pronounced. Here the artist presents the body of the saint as a perfectly bifurcated hermaphrodite— black male/white female—shot through with the arrows of social proscription against interracial relations, and tethered to its “Others”: a white male and the black female whose disembodied heads free float above in the background. Colescott is clearly less optimistic in this composition because while we see the main couple at the lower right in postcoital tenderness, at the lower left we see the silhouetted forms of a Ku Klux Klan gathering where the black man is being beaten. The mood of the white man at the left is reflected in his grimace, a clenched fist, and a broken cross outlined near his head, which, along with the broken heart over the black woman’s head, speaks to the fact that what is at stake is not the relationship between the white male and the black female. Rather, the subject matter is still centered on the long-standing sexual power dynamics between the races in the wake of slavery in which the focus was on taboos around relationships between black men and white women.

The Knowledge of the Past is the Key to the Future painting cycle coincides with Colescott’s residency at the Roswell Foundation and his move to Tucson to teach at the University of Arizona. His gallery representation became a key factor in ramping up his reputation and the dissemination of his work to private collections and museums. He began to show with Semaphore Gallery in New York in 1981, and moved to Phyllis Kind Gallery in 1987; she remained his primary dealer until her retirement in 2008. During this period, he continued to show with Koplin Gallery in Los Angeles, Rena Bransten Gallery in San Francisco, Laura Russo Gallery in Portland, as well as with Arthur Roger Gallery in New Orleans, Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle, N’Namdi Gallery in Detroit and Birmingham, Michigan, and LewAllen Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico. His work was also increasingly seen in such international venues as Laforet Museum in Tokyo (1985) and the Museum Overholland in Amsterdam (1990).

© Robert Colescott Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In 1987, the first retrospective of Colescott’s work, covering the years 1975 through 1986, was organized by the San José Museum of Art under the leadership of director John Olbrantz. In many ways, this exhibition was Colescott’s formal debut to a more general audience and a litmus test for the tolerance of the larger art world and the public for his painterly histrionics. The exhibition had a two-year tour and was shown in Cincinnati, Baltimore, Portland (Oregon), Akron, Norman (Oklahoma), Houston, New York, and Seattle. The catalogue included an analysis of the work in the exhibition by this writer, and a refreshingly frank and confessional memoir by Mitchell Kahan (then the director of the Akron Art Museum) that laid bare the conundrum of the forbidden pleasure of enjoying the transgressive humor around race and sex in Colescott’s work.

While the exhibition was still on view at the San José Museum of Art, the critical reception indicated the gist of subsequent reactions to Colescott’s work throughout the tour. Kenneth Baker acknowledged that the “raucous content” was in evidence “years before it became fashionable for reintroducing dashes of narrative, confession, satire, and social criticism into contemporary painting.” [25] Mark Van Proyen cast a jaundiced eye on Colescott’s high jinks, characterizing the painting between 1975 and ’83 as “poorly painted,“ relying on “a cartoonish sense of line” that seems “relatively tame and circumspect in comparison to the works of his contemporaries such as James Albertson, Roy De Forest, or Peter Saul.” [26] But in the end Van Proyen noted that Colescott “juggles the comedy of manners in order to mock the implicit mythologies those manners are symptom of.” [27] A review in the New York Times of his concurrent exhibition at Semaphore Gallery in New York noted that Colescott “knows that the ship of civilization is sinking yet he remains on board.” [28] It is a situation where the reviewer sees Colescott as not having much choice as he is “lashed to the main mast by history, like everyone else, but as a black man more tightly.” [29] “Besides,” the reviewer notes, “the painter believes that the ship’s passengers might as well go down better informed than they floated, and to that end practices what he calls ‘preachers’ expressionism.’” [30]

Dorothy Burkhart noted in the San Jose Mercury News that detractors of his work—particularly in the black community—“argue that Colescott doesn’t expose stereotypes, he promotes them.” [31] Indeed the exhibition did incur resistance from the black community at several venues, including the Akron Art Museum. Mitchell Kahan, who was director of the museum at the time, remembers:

Somebody got ahold of a catalogue in advance and showed it to a city council member, who attacked the museum in a council meeting, which of course made the papers. Thank goodness for the young artists in town…One young man in particular [William Fort]…painted a mural on Main Street defending Colescott. [32] Editorial cartoonists got into the fight too. By the time the show opened, about 1,200 people showed up for the vernissage, and Bob had to give multiple gallery talks until he was worn out because there were so many people. In retrospect, I was naive to present that material and not have expected what occurred, but it was an important lesson. If you believe in someone’s work, just do it and take the consequences. [33]

In Baltimore, the press reception of the exhibition began to explore notions of the dynamics of satire and how time had changed the reception of these paintings both positively and negatively. [34] There were reviewers who saw his work as a “manifestation of a deep-seated frustration as a black man in America,” [35] and others, like Ken Johnson, writing in Art in America, recognized that beyond racism,

[i]mplicit in his work is a much broader cultural critique, an argument against the tendency of Western culture to discriminate not only racially but in all sorts of ways between what it designates as superior and what it designates as inferior. Creating a purposefully comic wedding of cultural extremities in his parodies of celebrated paintings, Colescott shocks us into an awareness of a kind of psycho-cultural apartheid that persists in the American collective consciousness. [36]

The retrospective coincided with a key turning point in Colescott’s work. As Miriam Roberts observed, his work continued to show his mastery of “counternarrative daggers, pointed at the heart of authority and conventional wisdom, subverting conventional views of reality and exposing the delusion and the denial so deeply ingrained in culture and society.” [37] But his subject matter became even “more allegorical in connotation…[and]…the structural organization of his paintings assumed a more emphatic role in conveying his message.” [38] He deployed devices such as “the cut-away, the dream-sequence, the montage” [39] that predicate the organization of narrative elements and sequences in paintings such as Grandma and the Frenchman: Identity Crisis (1990) and A Visit from Uncle Charlie (1995). Both compositions are about determining one’s racial makeup, particularly when one is in denial.

In Grandma and the Frenchman, the black and white figures exist in a more forensic relationship as the main figure of a woman literally “unpacks” those racial dynamics in her head, which explodes into myriad racial identities in a stylistic manner that recalls classical Cubism. In an obvious reference to the particularly miscegenated society of Louisiana, the possible couplings that formed her ancestry are seen to the left and the right, with the white male and the blonde, black woman and the white (or octoroon?) blonde woman with the black male. But the presentation of the black female with a saw literally cutting through her head at the same time that a white hand with a hatchet takes aim at her indicates that all is not well.

In A Visit from Uncle Charlie, the main character becomes the literal “dark sheep” of the family who emerges from the closet to blow the covers of his relatives who are trying to pass for white. Colescott had previously played with notions of skin color and race in his Shirley Temple Black and Bill Robinson White (1980), where the title and the subject matter exploited the convenience of Temple’s married name—Black—to achieve his code switch with regard to the racial identity of the two well-known protagonists. Susan Gubar, professor of English and women’s studies at Indiana University, suggests that:

As in so many of his other paintings, this picture converts characters traditionally portrayed as white into blacks, switching the races so as to ridicule, first, our assumptions about white hegemony in cultural scripts and, second, the caricaturing that infects almost all depictions of African Americans in mass-produced as well as elite art. [40]

Gubar notes that Colescott’s self-described “one-two punch” in this instance “pertains to the shocking stories it uncovers about race and sex” and “the significance of the race changed child in terms of sexuality, lineage, and cultural empowerment.” [41]

What Lucy Lippard characterizes as a “sheer optical and sensuous enjoy-ment” in the work of Richard Pousette-Dart [42]—another art world maverick who, like Colescott, bridged the Abstract Expressionist, Color Field, and neo-figurative generations—can be seen in the new intensity of Colescott’s color in the 1980s and 1990s. Colescott’s work displayed what one former student at the San Francisco Art Institute, Leon Dockery, describes as a “lusciousness,” a particularly rich and textural surface. As seen in the previously mentioned works 1919 and Lady Liberty, the narratives are set against multicolored maps of the United States on islands of litter-strewn pink clouds. Colescott’s technique is comparable to that of the Renaissance cangiantismo, where shifts of hue create the midtones and lights in the modeling of the figures, creates a relatively uniform saturation of hues. [43] It is anti-naturalistic and allows Colescott to maintain a modernist preoccupation with the surface of the canvas while working with figural elements.

If, as Lippard wrote, “the surface is a metaphor for the intention” [44] in the case of Pousette-Dart, then in Colescott’s work, as Jody Cutler notes, “shapes and forms seem interwoven rather than existing on a plane,” and the “spontaneous act of painting” meets the “conscious form of content. [45] This is particularly true in Change Your Luck (1988) and Feeling His Oats (1988), where the figures and elements in the narrative abut one another like puzzle pieces while eschewing pictorial modalities such as perspective, relative scale, and proportion. At times, forms emerge from one another, as seen in the large head of the figure wearing a red shirt in Change Your Luck, or the disembodied hands brandishing a curved rod in Feeling His Oats. Colescott distributes color, pattern, and form across the composition in a manner that is independent of any narrative function. The artist himself noted that he was “leaving clarity behind and moving on to contradiction and ambiguity.” [46] As I noted in a previous essay, Colescott would also caution us to remember “how important memory is as a source for his imagery: that he is not after how a persona actually looks, but more a feeling for what he knows about how a person looks to him.” [47]

Colescott would continue to parse the reality of the American Dream in a number of paintings in the 1980s and ’90s. Three paintings from 1980—1919, his portrait of Miss Liberty and Tea for Two (The Collector)—show various social aspirations from migration in pursuit of a better life, to the presaging of the crowning of Vanessa Williams as the first black Miss America in 1983, and the emergence of a black collecting class in the global art market. Colescott’s well-touted embrace of the “absurd and grotesque” [48] is still palpable in the execution of these images. Underneath this veneer of diffidence is a deep-seated desire for acceptance and recognition—on the part of both the artist and his characters. In the later 1980s, Colescott brought a number of aspirational platitudes to his anthology of American tales. In the aforementioned Change Your Luck and Feeling His Oats, as well as Marching to a Different Drummer (1989), Colescott captures the follies and the perils of following the trail of the American Dream in a series of images that capture a variety of professions—blue collar and white—along with a number of obsessions and not a few talismans.

One of the most intriguing compositions of this period is School Days (1988). Despite the assertive representational character of the individual figures, the relationship between them is random. Scale and perspective are immaterial, as we see the outsized reclining figure with a gunshot wound in his chest to the right, a male student nonchalantly pointing a gun at the viewer on the left, and the anomalous bicolored nude female who dominates the space just off center. Her large head on a relatively slim body is eerily reminiscent of one of Gauguin’s figural sculptures, such as Tahitian Girl of 1896. Only Colescott could possibly combine in one painting a quotation from an obscure work of art and what has since become the particularly timely issue of school shootings.

In 1996, Colescott was chosen to represent the United States at the 1997 Venice Biennale. Miriam Roberts, who had been curator at the San José Museum of Art at the time of the 1987 retrospective, organized a presentation of his subsequent work, produced between 1986 and 1996. In the accompanying catalogue, Roberts notes that the concerns that had previously “impelled Colescott” and which “had been at the periphery of mainstream art now found themselves at its center.” [49] Thus, his work “began to find a wider audience during the late 1980s.” [50] The reception of Colescott’s work was now predicated by the emergence of neo-Expressionist painting, “which re-energized [painting] through just the sort of union of figuration and abstraction and exploration of personal identity in which Colescott had long been engaged.” [51] Roberts also brings Emil Nolde and Philip Guston to the roster of Colescott referents, and notes further the prevalence of appropriationist art as a rubric of identity politics and multiculturalism, “which became part of a broader national dialogue.” [52]

The critical responses both to the choice of Colescott to represent the United States at the Biennale and to his work were unusually ambivalent even in a situation where there are always dissatisfied, dissenting sentiments in the art world. The New York Times critic Roberta Smith, who wrote that Colescott “turned in one of the more solid performances,” [53] noted that the artist “made history just by showing up.” [54] Writing in Art in America, Marcia E. Vetrocq regretted the fact that considering “the length of Colescott’s career and his sheer orneriness as a political artist” that his selection was routinely dismissed . . . as a ‘politically correct’ choice for America.” [55] She also noted the opinion that “the artist was too provincial for fact-track international exposure.” [56] Writing in Art Monthly, Patricia Bickers reiterated the opinion that the choice of Colescott was “cynical” and “patronsing [sic],” and that the “serious problems that are overdue for resolution...cannot be solved by exporting them.” [57]

In addition, the developments in his work during the 1980s and ’90s left Colescott vulnerable to opinions of “conservativism” by critics such as Allan Schwartzman, who described the works presented in Venice as “kind of competent American regionalist narrative painting.” As compared to the more saucy and sassy work of the 1970s, Schwartzman found the recent paintings “confusing...[a]drift on their own agenda.” The exhibition, he said, “failed to present Colescott the myth-slayer, instead mounting a…show that fostered a myth of Colescott—the belated master!” [58] On the other hand, the New York Times critic Holland Cotter argued that Colescott “still has a lot of things to say,” that “over the years he has found new ways to say them,” and noted that his art in the 1980s began to show “more complex scenarios of his own invention.” [59] And a reviewer in the New Art Examiner would note that “Colescott’s work...was a welcome reminder that what seems to be the most traditional can be most subversive.” [60]

Part of the jaundiced reception of Colescott’s work might be due to the postmodernist fatigue that had infected the art world by the late 1990s, and the greater prominence of installation, performance, and media-based work. Although his work continued to be contextualized in postmodernist appropriationist strategies, Colescott adamantly saw it within the context of modernism. In the statement he prepared to accompany his 1987 composition Hard Hats in the Venice Biennale catalogue, Colescott noted he was interested in “the multiple realities created by geometry,” which for him was a hallmark of Cubism. [61] This composition is an homage to the postwar “construction worker” paintings by Fernand Léger (in whose Paris studio Colescott worked in the late 1940s) and features a woman visiting her construction worker husband on-site. The scaffolding that creates the framework in such paintings as Léger’s Builders with a Rope is mirrored in Hard Hats by the placement of the wooden beam hauled by the black worker and the planks of wood suspended from an unseen crane that mimic the horizontal and vertical alignment of the windowpanes.

While he “eschews the French master’s pristine precisionism…[Colescott’s] celebration of ordinary people in their pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness—the American corollary to ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité—indicates how Léger and Colescott share political terrain.” [62] Even a painting as subversive in subject matter and composition as the 1981 “Le Cubisme”: Chocolate Cakescape declares that allegiance. Essentially a bulimic pile of slices of chocolate cake with pink (strawberry) icing that fills the composition up to a glimpse of a blue sky at the top, it shows the slices as a seemingly helter-skelter arrangement of various triangles that mimics the “fragmented planes, shallow space, and all-over pattern of lights and darks” [63] seen in works such as Dancers at the Spring (1912, Philadelphia Museum of Art) by the renegade Cubist Francis Picabia.

The fraught reaction to the 1997 Biennale did nothing to deter Colescott from his artistic course. He continued to “challenge stereotypes, explore race and gender identity, and reclaim history” as he had in paintings from earlier in the 1990s, such as Arabs: The Emir of Iswid (How Wide the Gulf ?) (1992) or Choctaw Nickel (1994). In a work contemporary with the Biennale, Venus I (1996), Colescott revisits earlier compositions and themes from such works as Bad Habits (1983) and Listening to Amos and Andy (1982).

In Venus I, the nude, who lounges horizontally in a bubble space in Bad Habits, is seen sitting on a bench with her back to us. She is looking at a mirror in which a black woman stares back, continuing Colescott’s ongoing examination of issues of beauty and race. [64] While Colescott depicts himself at the easel capturing his Bad Habits, the easel in Venus I takes on a human form, with the easel’s legs supporting a painting and a palette that form the torso from which two paintbrushes dangle like arms. A second palette on top serves as the head. Colescott himself may appear as two specters in this painting: the disembodied Cheshire Cat grin with a stogie clinched in its teeth, or the rather sketchy repoussoir figure at the lower left that is reminiscent of Picasso’s self-portrait cameos in his own work. As in Bad Habits, Colescott created a convergence of perspective at the center, here with the floorboards and the checkered tablecloth forming a sharply diagonal transition between the foreground and the middle-ground of the composition.

Beauty is Only Skin Deep (1991) and Exotique (1994) demonstrate the continuing virtuosity with which Colescott approached figuration and compositional organization. In the first, a spectral couple rendered in black with red accents floats among the pink clouds like some extraterrestrial life form. Within the cloud and below in the far-left corner, there are Cubistic faces that combine frontal and profile views together, and to the right is a brown, tribal-like head that covers its face with hands of a lighter hue. Crammed in between all this is a multicolored map of the African continent and a landscape with a brown path leading through greenery to distant purple mountains under a blue sky. In Exotique, a large purple nude with a demoiselle-esque face and red-striped hair and leopard print panties floats against a radiating yellow, green, and red pattern. A rather anthropomorphic black feline nuzzles at her feet as she declares in a dialogue bubble: “Yo tambien!” We can assume that her “me too” declaration is in response to a stylish black woman in a kente cloth dress who responds, “*S.V.P, Cher Monsieur…Afrocentrique” to the Latin lover type who declares flirtatiously “Vous etre tres exotique…Chere Madame!!” At the lower left, a hapless black figure declares something in Arabic to the redheaded nude woman.

True to Colescott’s way, these works are unaccommodating and challenge us with all the arcane references, while at the same time they liberate our own interpretative faculties. A triptych from 1998, Alas, Jandava, is more esoteric in character, rendered in style reminiscent of childlike scribbles. The cast of characters might include, on the far left, his then partner Jandava Cattron (whom he met in 1996 and married in 2007), who is taunted by a redhead who might be Colleen Hench, whom he divorced in 1992. The central panel features a rabbit-like doll held by a blue woman and in the right panel forms are reduced to an extreme abstraction. These works coexist with other late paintings that are more abstract in character such as Pick a Ninny Rose (1999) and Sleeping Beauty? (2002), where form, color, gesture, and blank space come together to create compositions that are dreamlike and nightmarish at the same time. It would seem that Colescott is allowing his subconscious to roam freely in an unresolved way that both morphologically and compositionally relate to the character of his paintings in the first few years of the twenty-first century.

In the catalogue of Colescott’s third ten-year survey exhibition at Median Gallery in San Francisco in 2007, Daniell Cornell contextualizes Colescott’s artistic enterprise within the phenomenon of the carnivalesque put forth by modernist critic Mikhail Bakhtin. Interpreting blasphemy and transgression in the artist’s work as a “rebellion against prevailing norms,” Cornell provides a precise description of how Colescott seduces us into understanding the dynamics of power while “reversing standing hierarchies” by “celebrating the repressions on which those hierarchies rely.” [65] Cornell decides that this engagement of the carnivalesque allowed Colescott to create spaces where he could “imagine and even enact” an “unofficial version of society.” [66] In the end, Colescott mobilized the theoretical, critical, and morphological elements we associate with the “modern” and the “avant-garde” as fodder for his critique of postmodernism. He not only represents but also indicates possible paths of resistance and creativity, for groups of artists who are marginalized or eliminated from the story of art because of their race, gender, economic condition, political, and/or social status. Therefore, his career has never been more relevant than at this present moment in time. Given the crisis of race relations, image management, and political manipulation in the current American—indeed the global—landscape, Colescott’s perspectives on race, life, social mores, historical heritage, and cultural hybridity allow us a means—if we are up to the task—to forthrightly confront what the state of global culture will be in the next decade.

[1] Thomas Micchelli, “The Use and Abuse of Paint: ‘Fast Forward’ at the Whitney,” Hyperallergic.com, January 2017. Accessed July 10, 2018. https://hyperallergic.com/ 354618/the-use-an-abuse-of-paint-fast-forward-at-the-whitney/.

[2] See https://whitney.org/Exhibitions/FastForward. Accessed July 10, 2018.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Moira Geoffrion, transcript of Colescott research meeting at the Tucson Museum of Art, January 29, 2018. This is one of five meetings convened between September 2017 and March 2018 in San Francisco, Portland, Tucson, and Cincinnati that were funded by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

[5] Indeed, in many ways the work of the 1980s has a way of alluding to that period of Colescott’s work in terms of the themes, composition, and references. For example, the 1982 A Legend Dimly Told (p. 2) compositionally takes on the metanarrative of Auvers-sur-Oise (Crow in the Wheatfield), 1981, where the deconstruction of van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows of 1890 is balefully observed by a large head of the master himself. Then the title of this work recycles that of a 1961 painting (p. 49) that presents a version of an idyllic scene of a male and a female nude in a secluded swimming hole; this locale in turn reappears in Colescott’s Bather series of 1984–85.

[6] Linda McGreevy, “Robert Colescott,” Arts Magazine (November 1987): 94.

[7] The artist mentioned this many times over the years in conversation with the writer.

[8] John Dorsey, “Colescott’s Art of Race Relations,” The Sun, May 27, 1997, p. 3D.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Holland Cotter, “Unrepentant Offender of Almost Everyone,” The New York Times, June 8, 1997, p. 35.

[11] This garment may be seen as a “cache sexe,” which denotes notion of propriety in certain African societies. In her 1999 publication Black Venus: Sexualized Savages, Primal Fears and Primitive Narratives in French (Chapel Hill, N.C.: Duke University Press), T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting suggests that the “cache sexe” is an approximation for an apron or a tablier in French, which was a punning, pseudo-scientific designation for the alleged overdeveloped labia of the Hottentot female, as in the case of the ill-fated Sara Baartmann (pp. 27–29).

[12] Jody Cutler notes that the brassiere evokes the advertising campaigns for Maidenform bras in which a woman would find her “natural” state. Jody Cutler, “The Paintings of Robert Colescott: Race Matters, Art and Audience,” PhD dissertation, State University of New York at Stony Brook, 2001, p. 194.

[13] Joe Lewis, “Those Africans Look Like White Elephants: An Interview with Robert Colescott,” exh. cat. (New York: Semaphore Gallery, 1981), n.p. This interview is reprinted in this volume, pp. 203–06.

[14] Widespread legislation banning interracial marriage in the United States was not struck down until 1967 by the Supreme Court ruling in the landmark Loving v. Virginia case.

[15] Quoted in Robert F. Knight, “Robert Colescott: The One-Two Punch,” in Robert Colescott: The One-Two Punch, exh. cat. (Scottsdale, AZ: Scottsdale Center for the Arts, 1995), n.p.

[16] Kenneth Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1956), 205.

[17] See ibid., 109, 148, 173–77.

[18] I thank Malcolm Bull, who was a fellow at the Clark Institute of Art in spring 2007 with me, for this reference.

[19] Robert Colescott quoted in Lowery Stokes Sims, “Robert Colescott, 1975–1986,” in Robert Colescott: A Retrospective, 1975–1986, exh. cat., essays by Lowery S. Sims and Mitchell D. Kahan (San Jose: San José Museum of Art, 1987), 2.

[20] Quoted in ibid., 8. In the extended dialogue around the place of artists of color within modernism, Colescott’s comment echoes André Breton’s of the catalytic relationship between Picasso and Wifredo Lam after the latter’s intrusive arrival in modernist cycles. According to Colescott, Breton postulated an “inverse relationship between Picasso and Lam…each one starting at opposite ends of a scale from ‘civilized’ to ‘primitive’ and subsequently reaching a ‘similar state…by taking the opposite path.” André Breton, Le surréalisme et la peinture: Suivi de genèse et perspectives artistiques du surréalisme et des frag-ments inédits (New York: Bretano’s, 1945. Reprinted as Surrealism and Painting, trans. by Simon Watson Taylor (New York: Harper and Row, 1972), 181–82.

[21] Carrie Mae Weems, transcript of telephone conversation with Lowery Stokes Sims, March 8, 2018.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Robert Colescott, Collection Record, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

[24] Carrie Mae Weems, Framed by Modernism (Seduced by One Another, Yet Bound by Certain Social Conventions; You Framed the Likes of Me & I Framed You, But We Were Both Framed by Modernism; & Even Though We Knew Better, We Continued That Time Honored Tradition of the Artist & His Model), 1996.

[25] Kenneth Baker, “A Rebellious Spirit Lives On” San Francisco Chronicle, May 3, 1987, p. 13.

[26] Mark Van Proyen, “Inverted Stereotypes: The Paintings of Robert Colescott,” Artweek, vol. 18, no. 15 (April 18, 1987).

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Robert Colescott,” in Vivien Raynor, “Art: Show of Works by Tom Wesselmann,” The New York Times, April 24, 1987, p. 78.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Dorothy Burkhart, “Racism reversals in black and white,” San Jose Mercury News, April 3, 1987, pp. 1D, 14D.

[32] See Jim Carney, “Here’s a graphic defense of artistic freedom,” The Beacon Journal, June 2, 1988, pp. E1, E5.

[33] Mitchell Kahan, email to Lowery Stokes Sims, September 26, 2018.

[34] See Elisse Wright, “Robert Colescott: A Retrospective, 1975–1986,” The Baltimore Afro-American, January 16, 1988, p. 9.

[35] John Dorsey, “Robert Colescott: His paintings reflect the frustration of black artist in white America,” The Sun, January 17, 1988, pp. 1N, 3N.

[36] Ken Johnson, “Colescott on Black & White,” Art in America (June 1989): 149.

[37] Miriam Roberts, “Robert Colescott: Recent Paintings,” in Robert Colescott: Recent Paintings, exh. cat., essays by Miriam Roberts, Lowery Stokes Sims, and Quincy Troupe (Santa Fe: SITE Santa Fe and the University of Arizona Museum of Art, 1997), 20–22.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Lowery Stokes Sims, “Robert Colescott Redux,” in Robert Colescott: Recent Paintings, 32.

[40] Susan Gubar, Racechanges: White Skin, Black Face in American Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 203.

[41] Ibid., 203, 205.

[42] Lucy Lippard, “Richard Pousette-Dart: In One Light,” copy of a manuscript deposited at the Museum of Modern Art, 1969-70. Archives of Knoedler & Co.

[43] See http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110810104540225. Accessed May 17, 2007.

[44] Lucy Lippard, “Richard Pousette-Dart.”

[45] Jody Cutler, “The Paintings of Robert Colescott: Race Matters, Art and Audience,” 7.

[46] John Dorsey, “Colescott’s Art of Race relations,” p. 3D.

[47] Robert Colescott, conversation with the writer, May 11, 1997. This excerpt is from Lowery Stokes Sims, “Robert Colescott Redux,” 36.

[48] Michael Lobel, “Back to Front: Michael Lobel on Colescott,” Artforum (October 2004): 268.

[49] Miriam Roberts, “Robert Colescott: Recent Paintings,” 22.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Ibid., 23, 24.

[53] Roberta Smith, “Another Venice Biennale Shuffles to Life,” The New York Times, June 16, 1997, p. C1.

[54] Ibid., p. C12.

[55] Marcia E. Vetrocq, “The 1997 Venice Biennale: A Space Odyssey,” Art in America (September 1997): 72.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Patricia Bickers, “Last Exit to Venice,” Art Monthly (July/August 1997): 5.

[58] Allan Schwartzman, “An Impolite Question,” The Art Newsletter (September 1997): 72.

[59] Holland Cotter, “Unrepentant Offender of Almost Everyone,” p. 35.

[60] Unidentified Reviewer, New Art Examiner (September 1997): 23.

[61] Colescott quoted in Robert Colescott: Recent Paintings, 26.

[62] See Lowery Stokes Sims, “Robert Colescott Redux,” 32–49.

[63] See http://armory.nyhistory.org/dances-at-the-spring/. Accessed October 14, 2018.

[64] The mirror motif is reminiscent of a small 1943 drawing by the Cuban Surrealist artist Wifredo Lam, which shows his wife, Helena Benitez, looking at an avatar of herself in a hand mirror as one of Lam’s Africanized femme cheval. This was a potent image representing what Jean-Paul Sartre characterized in the early 1950s as the “more complete Africanization of Western art” that occurred in the wake of Europe having “accepted primitive art into itself ” and thus was “colonized in reverse.” Sartre quoted in Robert Linsley, “Wifredo Lam: Painter of Negritude,” Art History, vol. 11, no. 4 (December 1988): 553.

[65] Daniell Cornell, “From Jester to Gesture in Robert Colescott’s Late Paintings, in Robert Colescott: Troubled Goods, A Ten-Year Survey (1997–2007), exh. cat., essays by Anne Trueblood Brodzky, Peter Selz, Daniell Cornell, Albert Stewart, and Jandava Cattron (San Francisco: Meridian Gallery, 2007), 18.

[66] Ibid.