Blum & Poe Broadcasts presents free and public access to scholarship and writerly ponderings from our publications archives and network.

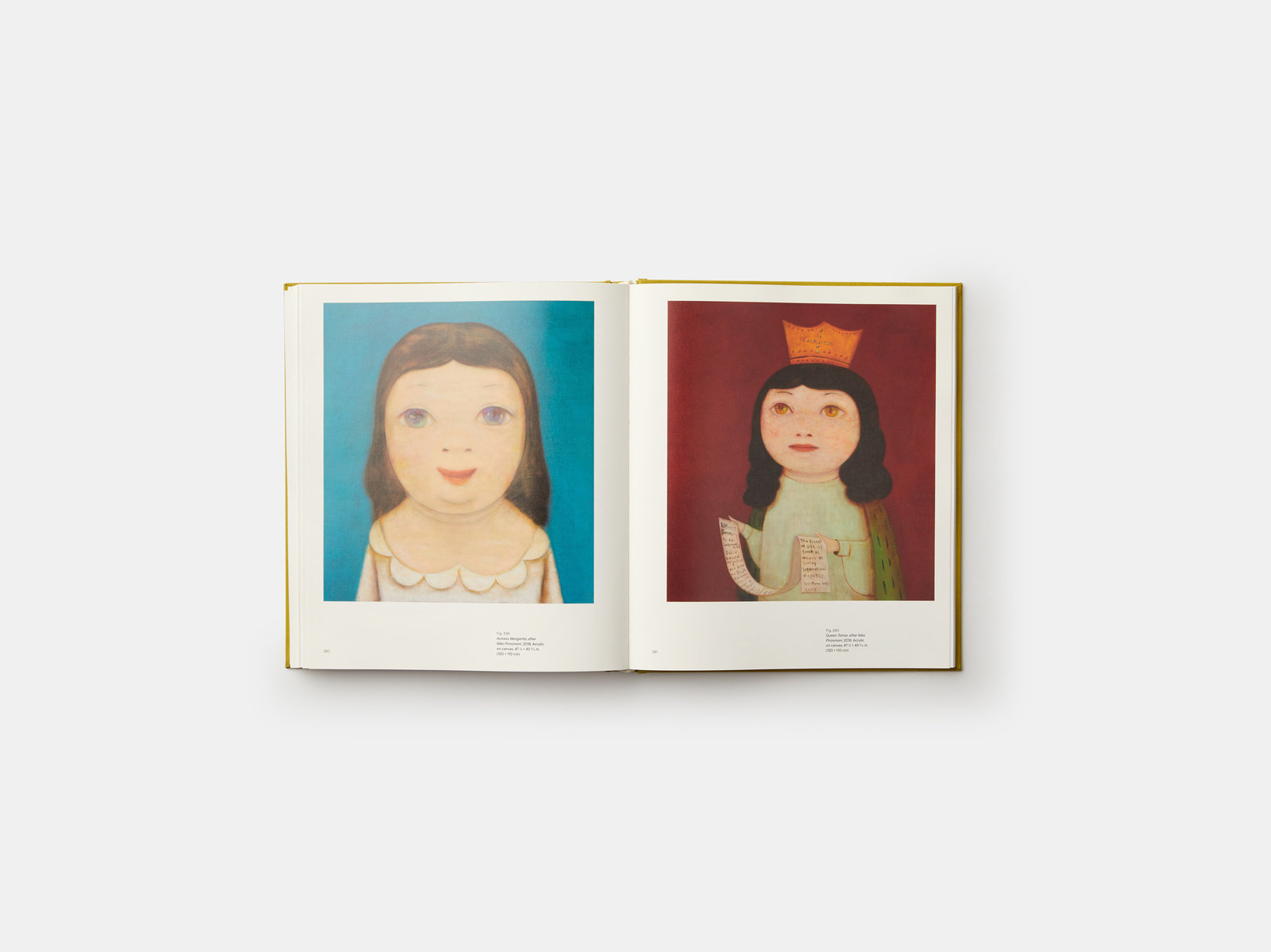

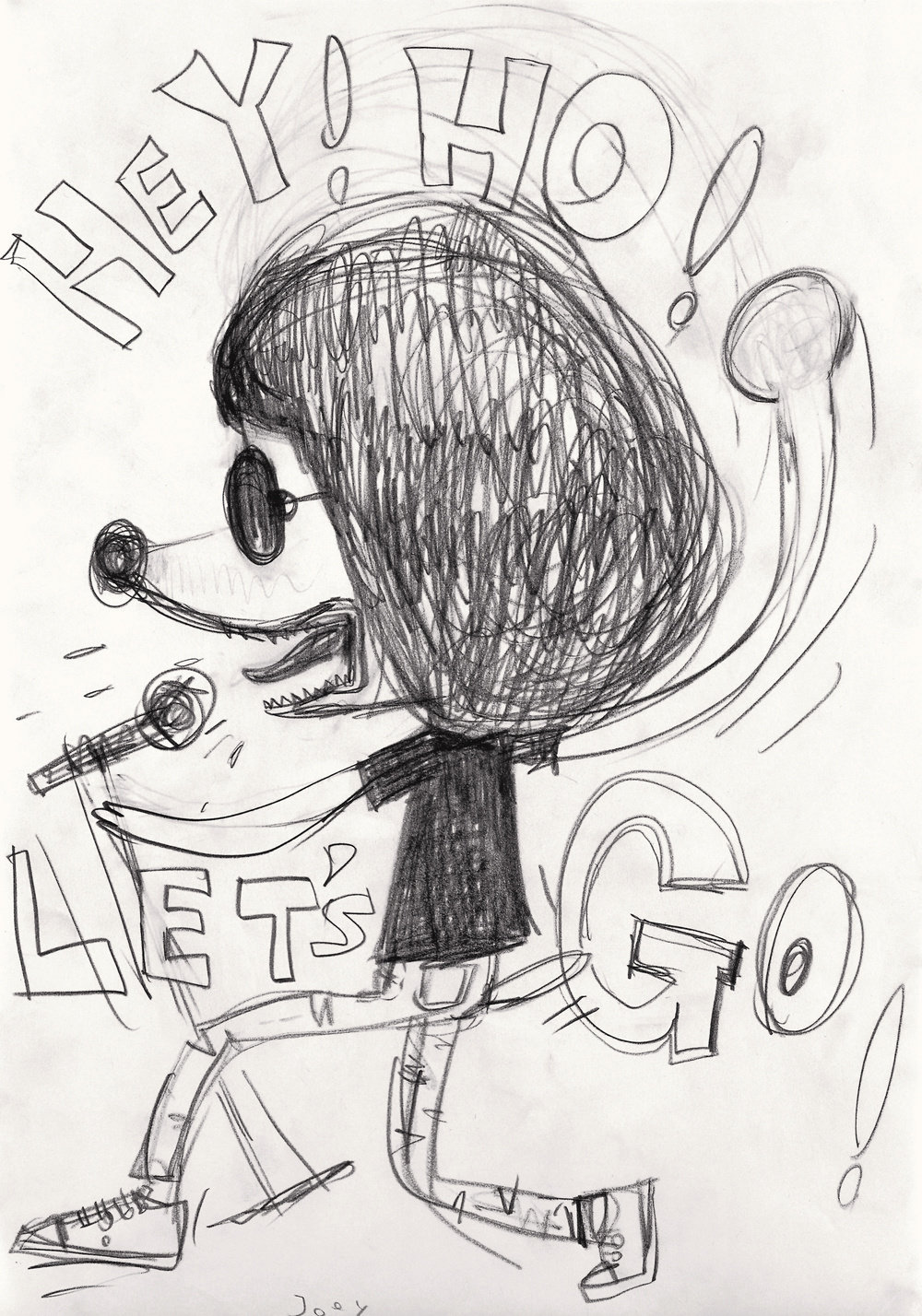

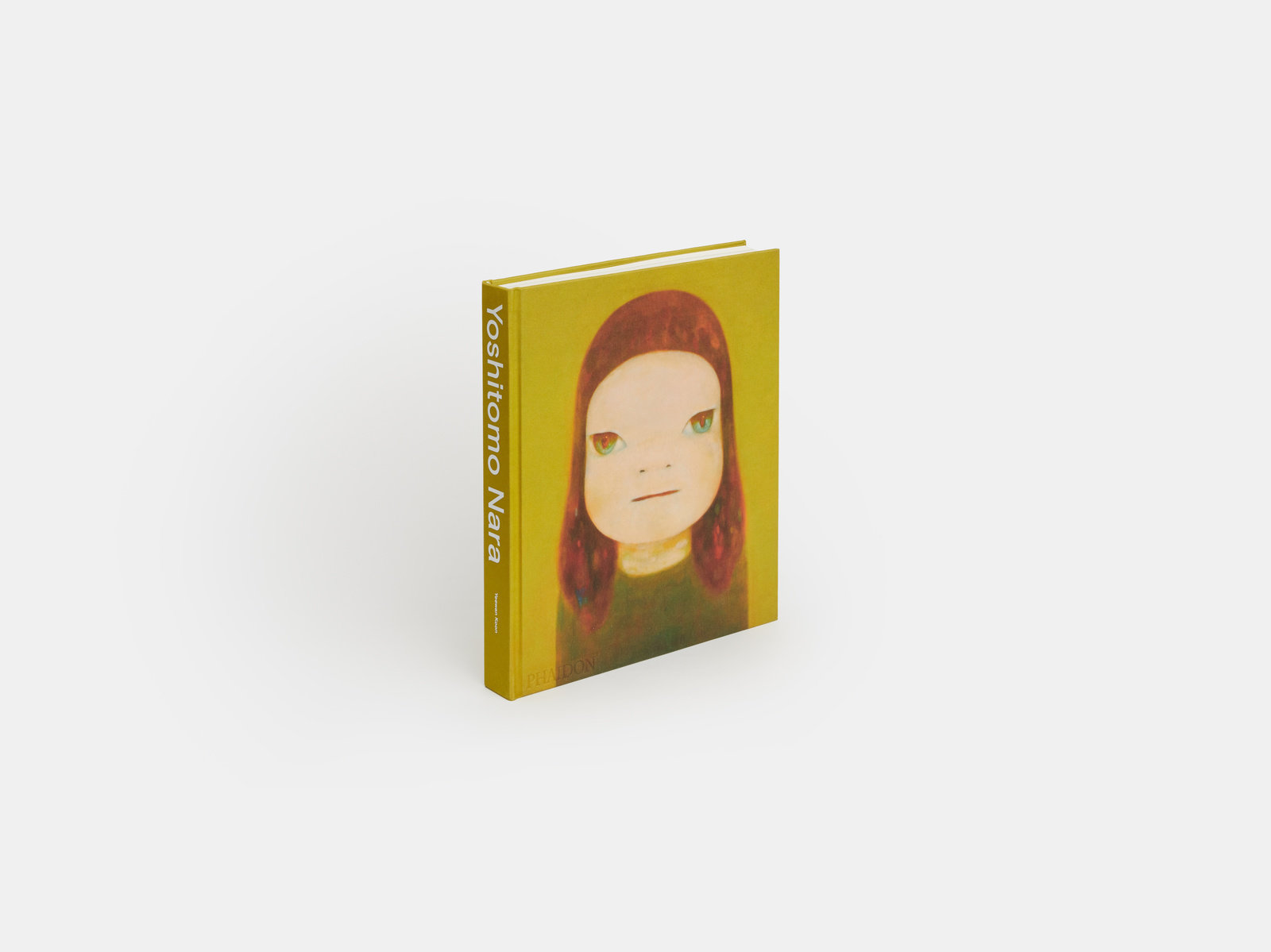

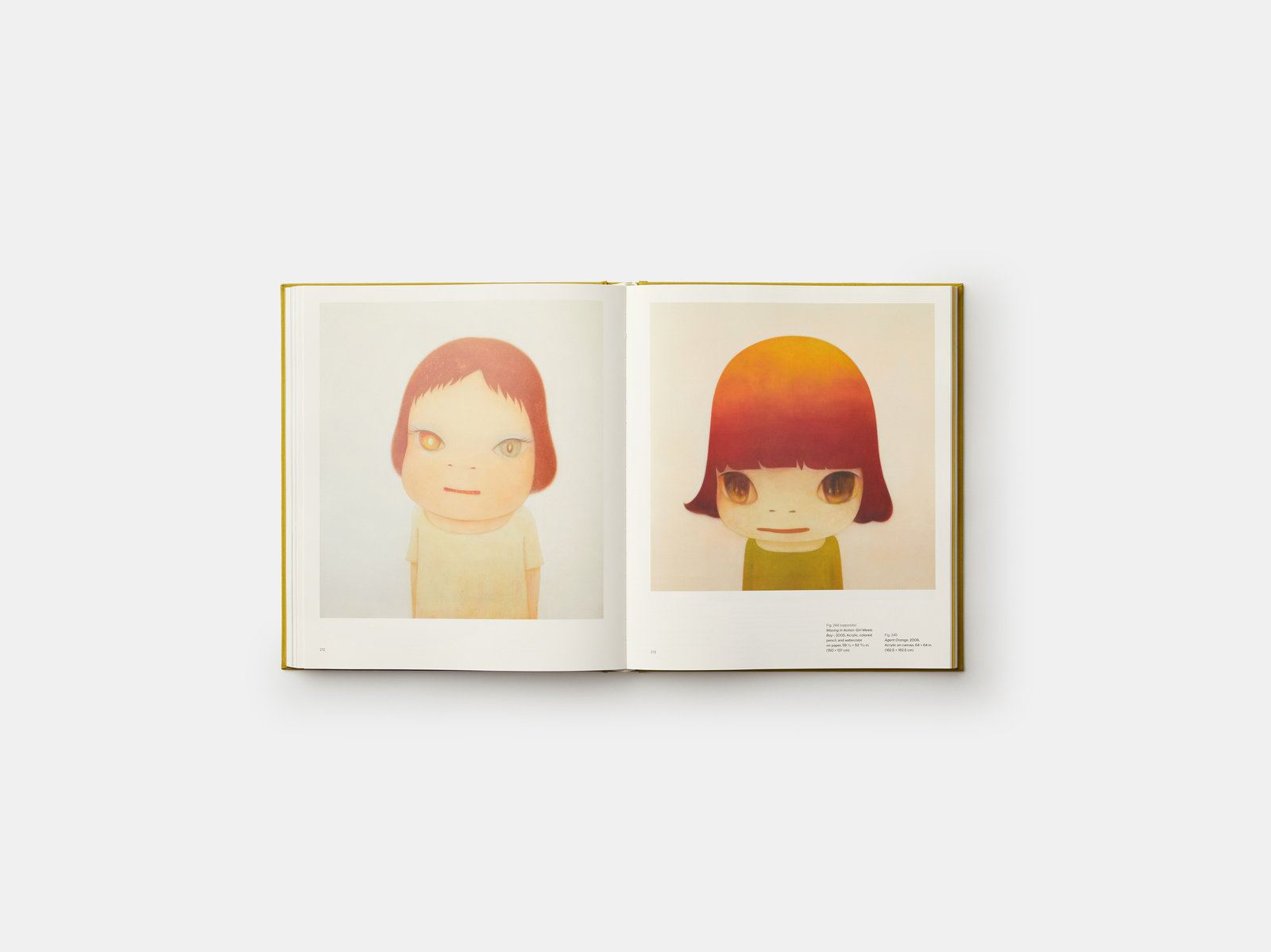

In focus this week—an excerpt from Yoshitomo Nara by Yeewan Koon (London and New York: Phaidon, 2020), a new monograph about the life and work of Yoshitomo Nara. This book covers 5 key themes of the artist's practice: the influence of music; his experimentations with his big-headed girl figure; his collaborative projects with artists and musicians; his relatively unknown photography work; and his more recent work that responds to the 2011 earthquake and nuclear disaster that affected his home region of northern Japan. The volume was made in close collaboration with Nara himself. From his early days as a student at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf through to the present day, Yoshitomo Nara covers the breadth of his work in painting, drawing, sculpture, ceramics, and photography.

More info on the book here.

It Started with Music

By: Yeewan Koon

From at least the age of five, Yoshitomo Nara spent a good deal of time in the mountains behind the shrine where his father and grandfather had once worked. His sure-footed scrambles through the dense forest demonstrate a childhood without much adult supervision. He had enormous freedom, and, although at times this brought him loneliness, he was rarely unhappy. Precocious and watchful, he invented his own games and found companionship with his neighbor’s cat. When he was six, together with a friend, he jumped on a train just to see where the tracks ended. But he was rarely reckless and seldom in trouble.

This freedom allowed Nara to escape the confines of his daily life, as did his love of music. At the age of eight, he built his own radio, which became a treasured companion and helped him understand that he belonged to a larger world. One night, half asleep, he woke up to unexpected music streaming through the family radio, and while it was in a language he did not understand, he was captivated by the melody and rhythm of the songs. Nara had unwittingly stumbled upon the music station of the nearby US Air Force base in Misawa. Thereafter, he would furtively tune in late at night, escaping into the thrills of American rock and country music.

Nara purchased his first single, by the popular Japanese band Takeshi Terauchi and the Bunnys, when he was only eight years old, an impressive feat given the remoteness of Hirosaki and the difficulties in gaining access to the latest music. [1] Hirosaki was approximately an hour away from the nearest city, Aomori, which is nearly 435 miles from Tokyo. Moreover, until 1979, the two cities were only connected by highways and small roads, which resulted in a time lag in the arrival of the latest fashions and trends. This only cemented the perception of the north as the remote, unsophisticated counterpart to Japan’s cosmopolitan heartland. For Nara, finding a newly released or hard-to-find recording was part of the excitement of transgressing such geographical boundaries. This was the first time he had purchased anything with his own money, and when he opened the door of the record store, he felt as if he were venturing into an illicit world of pleasures, terrifying and thrilling at the same time.

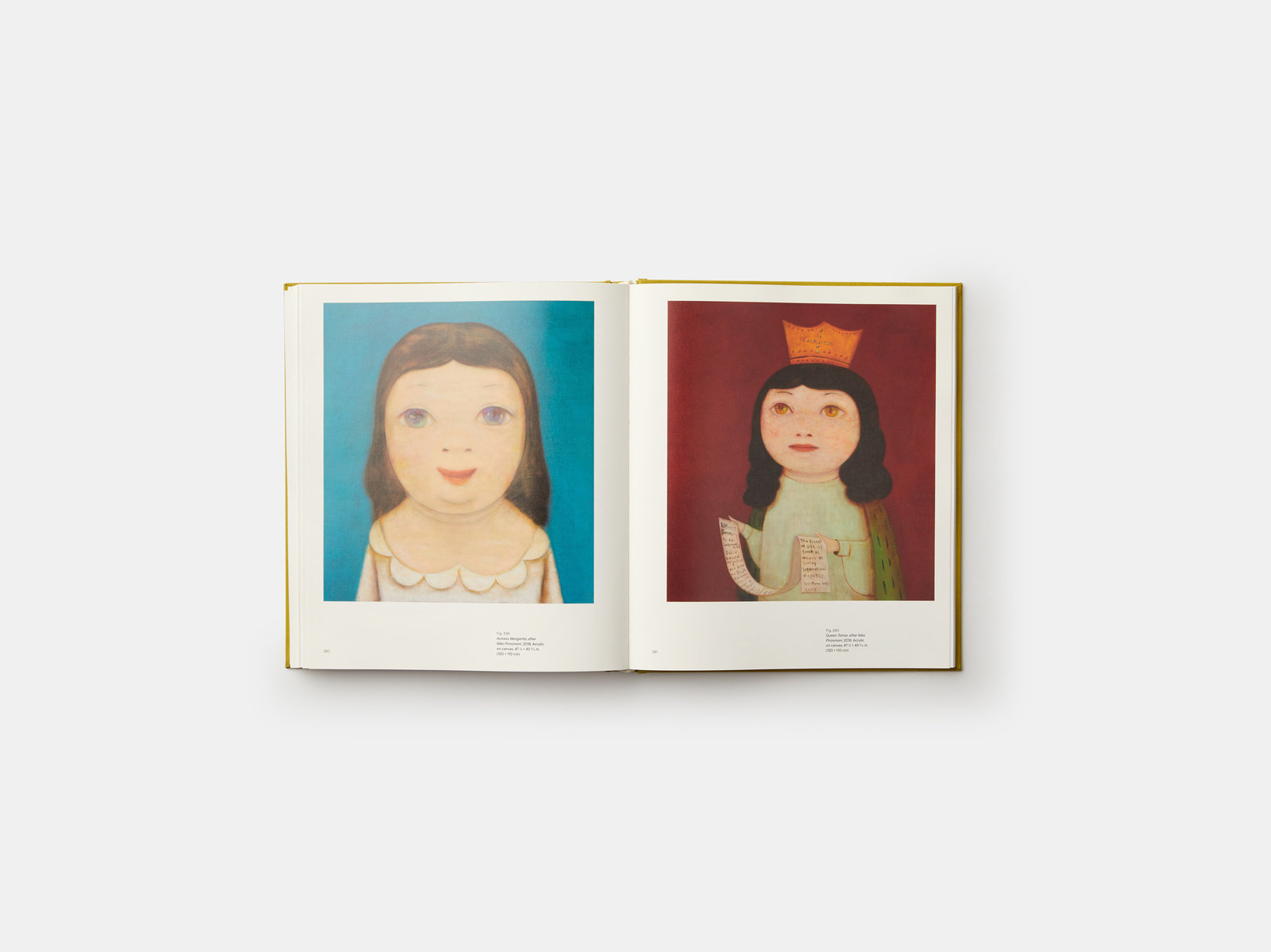

Nara consumed as much contemporary music as he could, from Terauchi to Janis Joplin, the Beatles, and Johnny Cash. He frequented the local university’s café to listen to new music, spent hours browsing through music catalogues, made drawings of album covers he purchased, and doodled away to his favorite tunes. The visual energy of the albums’ sleeves—the colors, the graphics, and the exoticism of foreign bands—provided great inspiration. It was these albums that took him into the world of contemporary visual and sonic arts, which, for Nara, went hand in hand. [2]

[1] Takeshi Terauchi (b. 1939) is a Japanese instrumental rock guitarist. He formed his first band, the Blue Jeans, in 1962, but left it in 1966 to form Takeshi Terauchi and the Bunnys. Their album Let’s Go Unmei (1967) was the band’s first hit and won the Arrangement Award at the 9th Japan Record Awards. Nara’s first record purchase was the title track from this album, which was released as a single. To this day, Nara still uses the phrase “Let’s Go” in many of his drawings and paintings. Despite the success of this band, Terauchi left the Bunnys and reformed the Blue Jeans in 1969.

[2] Living so far north, Nara did not go to his first contemporary art museum until he was eighteen. Growing up, he had no knowledge of—let alone access to—the vibrant postwar art world in Japan. During the 1960s, there were many new artist collectives, including Hi Red Center and Zero Jigen (Zero Dimension) in Tokyo, and Yoko Ono first performed her Cut Piece in Kyoto (1964). For more on performance art in Japan, see Thomas R. H. Havens, Radicals and Realists in the Japanese Nonverbal Arts: The Avant-Garde Rejection of Modernism (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2006).